I have always personally been a follower of calibres that started with the Holy Number Four, and that, in those days, usually meant .45ACP. I always carried a .45ACP. The calibre speaks with authority, is not difficult to master with a little dedication and practice, and is an absolute pleasure to reload. And with two exceptions mine was always emblazoned with the mark of the horse.

Interestingly, after being forced in 1985 to abandon their venerable M1911 .45 autos for the Beretta M9s in 9mm, the US Marine Corps across the board have finally gone back to the single stack .45s, manufactured by Colt Defense, Colt’s military branch. There is nothing whatsoever wrong with a single stack pistol, and IPSC’s Classic Division recognizes this. And I would argue any day that competitive shooting is very good practice, especially in terms of what can go wrong and how to rectify it.

There is some inherent human instinct to personalize possessions, and this seems especially pronounced with firearms, especially to make them competitive. They just never seem to be quite adequate straight from the factory. I’m as guilty as anyone in this regard, and one of the advantages of my competition pistol being my carry gun was that I only had one piece to tinker with. But of course competition and carry are two very different applications and so the disadvantage was one or the other was always a bit of a compromise.

Ross Seyfried once commented that the only two things a serviceable pistol needed were a good set of sights and a clean trigger. He is right of course, but I am left-handed, so I need an ambidextrous safety on a single-action self-loader. On a competition pistol, I will want as wide a safety as I can get – like the excellent ones from Ed Brown and Colt. With the pistol shoved into a small-of-the-back holster and being rubbed up against car seats and suchlike, a thinner Swenson’s or Wilson model is the way to go. An oversized magazine well is fine for a range gun, but on a carry gun it is less obtrusive if you simply bevel the lips of the magazine well. And so on.

I have never shot in any of the high-tech divisions, and so the gun I took to the range has always been acceptable for a carry piece. And then my friend Charlie Haley got me thinking. Charlie postulated starting a regular backup/hideout gun shoot. He was no doubt thinking of a not-insignificant number of our members who have little Walther PPKs, or Colt Detective Specials, and the like.

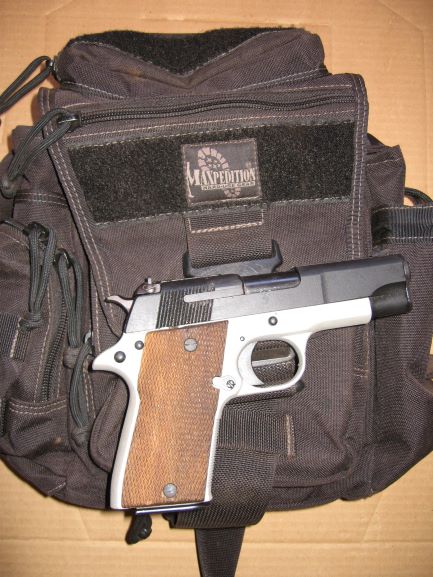

The seed that had started germinating in my mind was subtly different. What if my backup/holdout gun was my primary carry gun? I had lately had the chance to put a couple of the little Colt Officer’s ACPs through their paces, and I liked the feel, the weight, and their easily-concealable size. And, of course the calibre. Trouble was, they were all spoken for. That was when a gunsmith friend of mine casually mentioned that he had a spare Star PD in his stock. Not many rounds through it, but could have been looked after a little better. Good – a fixer-upper. Because I know I’m going to play around with it a little anyway.

It was a .45. It was a 1911-type, very similar to the one I shot every weekend. It was an alloy frame, and much more forgiving to lug around than a Colt Mk IV Series 70. The price was right. And I wouldn’t have to miss out on Charlie’s new shoots.

I had come across a few Star PDs in my time, but I had never really taken a close look. One thing they all seemed to have in common, though, was that their owners, hard-core gun-nuts each and every one, had sworn that the little .45 would be “the last gun I ever sell”. Superseded by the Firestar M45, they’re not easy to find these days. Col Jeff Cooper thought highly enough of them, but his advice was to buy one to shoot and one to carry – the aluminium frame can take quite a hammering from .45 hardball. Makes good sense if it’s going to be your only gun.

I checked out a few of the Internet forums, and the consensus seemed favourable: “I’ve had two. Both guns were very good, reliable shooters.” “Feather-light and just the right size for carry.” “They are good, reliable guns if the recoil buffer is in good shape.” “Mine was target-gun accurate, 2” or better at 25 yards.” “Very nice gun – good angle to the grip and parts are not that hard to get if you know where to look.” “To be carried a lot and shot a little.” “Light weight and goes bang every time.”

The nice thing about most forums is that you normally get the bad news up front and with emphasis, and there didn’t seem to be much. The recoil spring guide has a buffer similar to the Wilson type I use in my Colt, and that has to be kept new-ish. So far so good. I’m one of Bill Wilson’s best customers for recoil buffers, and my Colt and not the little Star will be taking the 50 rounds+ every weekend anyway. A lot of die-hard 1911 fans don’t like the recoil buffers. They have never given me any problems.

The little PD came with just about everything you’d want – except an ambidextrous safety for southpaws. A generously-sized ejection port – which it took Colt a long time to come to terms with – nice sights and a clean trigger.

When I’d first picked up the little brute, the first thing I checked was the slide stop hole in the frame – no cracks or deformation at all. .45 ammo never was all that easy for most folks to come by in Zimbabwe unless they were regular club members. I also checked out the recoil buffer and gave my gunsmith a Wilson one to fit. The magazine release spring was lightened just a little, and my ‘smith beveled the edges of the magazine well, but the only other attention it needed was a thorough cleaning of the innards and some polishing and re-bluing of the slide. The anodizing on the frame was a little rough around the edges, and my gunsmith showed me a re-work he’d done on Star’s 9mm counterpart, the BKS. He’d put a beautiful matte blue on the slide, and bead-blasted the frame. I was a little wary, knowing that anodizing is used to strengthen metal surfaces, and after a few queries I had learned that with reference to aluminium alloys, anodizing is done to increase resistance to corrosion, reduce friction and allow coloured dyeing, but not to increase the inherent strength of the part. I was still wary, as it seemed prudent to re-anodize the frame, but the quality of this process in Zimbabwe now was almost nonexistent. So, bead-blasted it was.

By the time I had put the beast through its paces with some light Winchester 185gr match ammo I knew I had made a good choice. Without the benefit of a grip safety or an ambidextrous safety catch I am going to have to content myself with carry in Condition 2 – having satisfied myself that the firing pin is definitely floating – but that’s what dry drills are all about, and I have never stopped doing them.

It’s all well and good to practice mainly with the Colt and carry the star, but there are subtle differences, and I have found that some range-time is essential with both. I load 5.0gr of Somchem’s S121 powder under a Frontier 230gr CMJ bullet for competition with my Colt, and that gives me an IPSC power factor of 174 at just under 760 feet per second. With most factory hardball claiming 850, the load seems light enough for occasional practice – and I’ve chronographed it out of the little PD at 744 fps which – for whatever it’s worth – still gives an IPSC power factor of “Major”. Carry ammo is Winchester’s 230gr SXT ammunition.

The emphasis today might be on firepower and high-capacity magazines, but there is something ultimately reassuring about seven rounds of .45 in your vest pocket.

(Originally published in MAN Magnum magazine)

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!