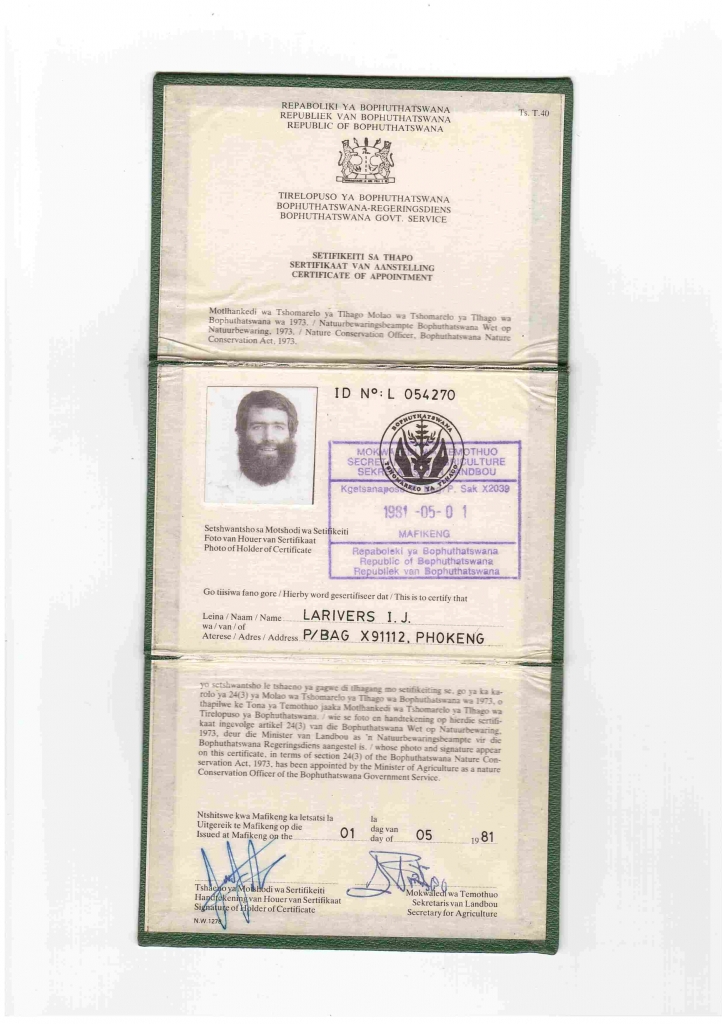

I J Larivers

OK, this is one where I get to combine my recreation – shooting – with the storyline. The Branch never did have what could be called an awe-inspiring collection of firearms to issue its details. This seemed to be a fairly universal state of affairs, for it had been the same in Bophuthatswana when I’d had to make do with a bolt action .243 on roadblock duties until I eventually confiscated some poor South African national serviceman’s FN-FAL that he had used to poach a kudu. Most of what there were bore the scars of apathy, neglect, and misunderstanding.

True fact: there aren’t as many “gunnuts” in law enforcement circles as you’d expect. A firearm is regarded as a tool. A means to an end that you hope you’ll never be confronted with. It is treated as a given that if you’re issued with a weapon system it will function flawlessly if required to do so and merely by carrying it around your own proficiency will mystically be somewhere between Marksman and Expert.

When I first joined the Branch, there was some marginal variety in sidearms. To gunnuts, this is not always a good thing. Unless you do a lot of training, it’s best to standardize. Especially in the matter of ammunition. I still smile when I recall the look of consternation on a colleague’s face when the .357 Magnum rounds he was trying to stuff into a .38 Special didn’t fit! Fortunately this was in preparation to go out into the field and not under more, shall we say, demanding circumstances.

In addition to one .38 and one .357, we had one .25 ACP, a couple of AK-47s, an FN rifle in 7.62mm NATO and a Stirling 9mm sub-machinegun. Six different calibres among a handful of weapons is not good. Not good from the standpoint of acquiring and maintaining stocks of ammunition and not good when it comes to interchangeability of firearms among different operatives. We did not have cleaning kits and these weapons probably last saw the friendly face of a gunsmith when they left their respective factories. The firing pin in the little .25 was jammed so far forward it was impossible to chamber a round, presumably due to having been “cleaned” with linseed oil or some such. But as the ammunition wasn’t generally available for practice, this was only noticed one day in the middle of a takedown. The goblins, happily, offered no resistance, being suitably preoccupied by the antics of the game scout racking round after round out of the magazine while an assortment of live rounds accumulated at his feet!

Change came when the .357 – a beautiful little Smith and Wesson Model 19 – was taken to the main police armoury for repair and it was noticed the rear sight blade had fallen out. Somewhere, sometime. This had presumably occurred as it was rattling around under the seat of the Land Cruiser on some bone jarring trip to one or another corner of the bush that God had long forgotten. The police superintendent, Charlie Haley – a good friend who was also a gunnut – took one look at the once-proud little Smith and Wesson and took all the Branch’s weapons in for ‘servicing’. Gunnuts have a tendency to become anthropomorphic about firearms. We sometimes even talk to them. And there was no way that a Smith and Wesson was going to be sent back to that lot! The result being that when we called around at the armoury a couple of days later, we were given a box of 7.62mm Russian Tokarev pistols that were already uh, well-used, shall we say.

But the Tok, like the AK is a legendary workhorse if not exactly a collector’s piece, and by African standards they had a lot of life left in them. Theoretically this solved the standardization and ammo compatibility problems. They had all been fired with corrosively-primed Soviet bloc ammunition, so the bores were far from immaculate, but that couldn’t be helped. Training however…well…

Following the arrest of a soldier with an elephant tusk, I came across a Tok that had been issued to the game scout, rattling around under the seat of the truck. Gone were the days of detention barracks for a negligent discharge, let alone drawing a firearm and then going off happily home having forgotten all about it!

The one major disadvantage of anything Eastern-bloc is that damn near all of their ammunition was corrosively-primed, and I thought that the brute might need a good cleaning, so I took it home. Why was I not surprised when I cleared it and found the magazine full of 9mm rounds? The ol’ “if it fits in the magazine, and the magazine fits in the gun, it’s gotta work” reasoning. (I figured that story was worth a couple of beers the following weekend at the shooting range, but I was put in my place by Charlie Haley, who told the tale of his investigating an armed robbery and homicide where they recovered 9mm cases and what he described as “long, thin” 7.62mm bullets – not only is the Tok a workhorse, it’s a damn strong one, for this is exactly what the robbers had done – the 9mm rounds fired, re-sized, and the pistol survived!)

This use of ordnance can easily be justified by “Well, that was what we have a lot of”, but the 9mm rounds not only fit the magazine, they fit the chamber as well, no doubt head-spacing on the extractor claw.

And that is why I always carried my own personal firearms, which was allowed, and which I had also done in Bophuthatswana. So – what were these guns, and why did I make those choices?

Firstly, there isn’t a lot of scope for long guns in undercover work, although when out and about for long periods in the Zambezi Valley we would often take a folding stock AK-47. In order to keep the goblins from seeing it, it had to be so well hidden that it could take an age to be brought into use, so its value was questionable. Secondly, I firmly believe that the only reason for anyone to carry a 9mm is because they haven’t learned to use a .45 yet.

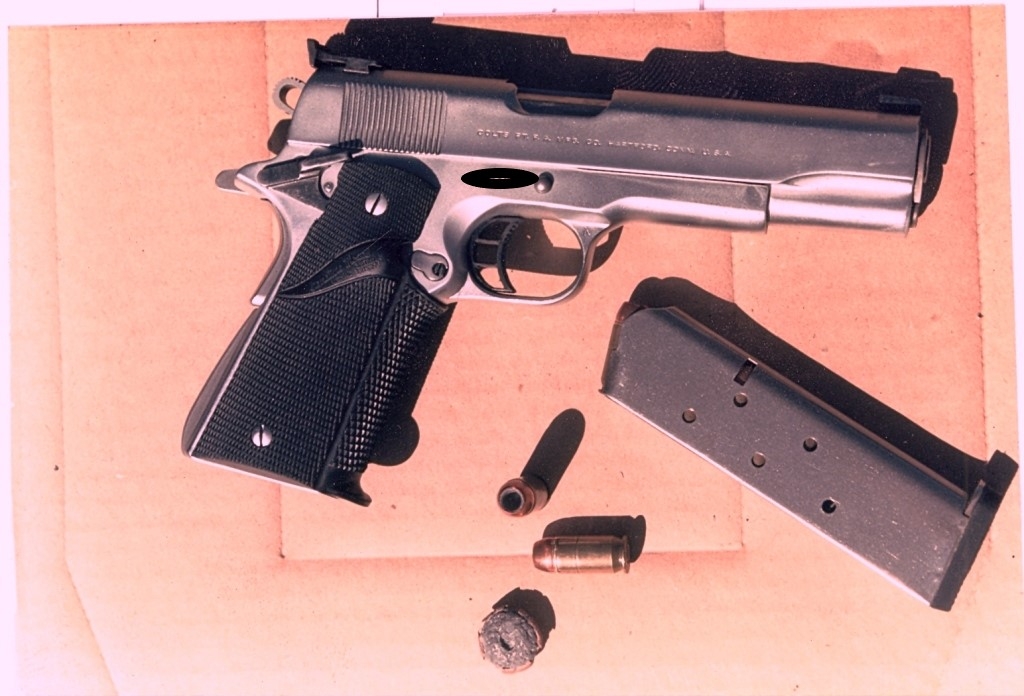

John Browning did a good thing when he invented the 1911 .45 pistol, now over a century old and still one of the most popular firearms in the world, and he must surely have gone to heaven for that very deed. Though it can be about as cantankerous a sidearm as ever saw the light of day, and must have the greatest consumer tolerance of anything wrought by the hand of man. But, once you’ve polished the feed ramp, throated the barrel, relieved the ejection port, made sure the barrel link is the correct length, tuned the extractor, fitted a decent trigger and set of sights, installed a lighter recoil spring, de-burred the safety catch and bought a few aftermarket magazines that actually feed rounds, it is The One.

Initially during the Rhodesian bush war (I was an ecologist with the Department of Veterinary Services) I’d carried a Colt Mk IV Series 70, and in Bophuthatswana a Colt steel-framed Combat Commander. Mine during the early days with the Branch was a Colt 1911A1 model, and it had seen plenty of use when I had bought it at an auction a couple of years previously. I had done all of the above. I had a good gunsmith friend, Nigel Wentworth-Browne, mate the feed ramp and barrel with just the right step, custom make a new barrel link, and take a couple of mm’s off the bottom of the ejection port and scallop its rear surface.

Rhodesia, South Africa and now Zimbabwe are different, and the custom work done here is first rate. I put in one of the then-new computer-prepped hammer and sear sets behind a carbon fibre trigger, fitted a set of high-profile Bill Wilson sights, and a new 16-pound recoil spring. Being left-handed, the safety catch was an Ed Brown ambidextrous one, and I clipped half a coil off of the magazine release spring to make it easier to activate with my left index finger. With a deep satin blue finish on the slide, and a hard chromed frame furnished with Pachmayr grips and mainspring housing, it was fit to grace the cover of any gun magazine. The suppliers of all the custom bits couldn’t have bought better advertising, because this was a real, live, carry gun in more than just the imagination. Whoever emptied out my trash can probably more or less had his own .45 by the time I was finished.

I shot local IPSC Practical Pistol matches with it, so I knew that it worked. But this was the era of the birth of high-capacity major power factor calibre frames, and even though I was using Bill Wilson’s fine eight-round magazines I was getting less competitive by the nanosecond. It wasn’t until 2012 that the single-stack pistols again became competitive in IPSC competition with the advent of Classic Division.

And since we’ve broached the subject of training, a word about the “practical” shooting sports. They aren’t. Practical Pistol hasn’t really been practical since the days of the Rhodesian and South African bush wars. Probably one of the reasons David Westerhout won the 1977 world championships was his time training with the Rhodesian SAS. Other disciplines, such as IDPA have tried to get closer to the mark, but whenever there’s a rule book involved, anything eventually becomes a game. I would often get back to the range after a trap, and design a course of fire around what had actually happened, as if it had gone pear-shaped. I would usually have to do this during the week when no one else was around, because of necessity most of the shoots broke every rule in the book and on the range – fortunately we had a couple of good 360 degree ranges.

IPSC power factor for ammunition is also pretty anaemic these days. It’s calculated by multiplying the bullet weight in grains by the velocity in feet per second and dividing by 1000 to give a wieldy three-digit figure. In the early days, any factor below 125 scored zero, anything between 125 and 174.99 counted as “minor” and everything above 175 scored “major”. “Major” has for some years now been reduced to a ludicrous 170 in most divisions.

Think about this for a moment. In order to “make major” with my .45, all I have to do is shoot a 230gr bullet at 740fps. No self-respecting ammunition manufacturer would produce rounds that didn’t send that bullet out at at least 850fps, lest they might not even reliably cycle a gun.

In the days before match chronographs, the organisers used a ballistic pendulum. My club, Harare Gun Club, still has one. A factory 9mm bullet was fired at a steel gong which moved a spring-loaded pointer up a scale. Competitors’ rounds had to equal that performance to be scored as “minor” and the process was repeated using factory .45 ammo to determine “major”. Thus, when men were men, &c., they were likely factoring around 195 to “make major” and the Rhodesians were known to sometimes use the somewhat more spirited FN .45 ammo to calibrate the pendulum – and those would have factored over 200. Again, the rule book says you need to differentiate between “major” and “minor” for scoring purposes in the game, but the all-important consideration – even with a .25 – is shot placement, and the numbers above really mean very little.

But, and it’s a very big but, regular range time in something like IPSC will show you every conceivable thing that can go wrong with your pistol, your mags and your ammo, and will train you how to clear malfunctions in your sleep. It will give you ultimate familiarity with your firearm, and cement the basics of good marksmanship. It will also inculcate a number of competitive, ‘gamesman’ tactics that are almost guaranteed to get you killed anywhere but on the range. Shooting well against an electronic timer is good, but doing the same against incoming fire is just something you’re going to have to pick up the hard way. My good friend former CID Detective Superintendent Charlie Haley, who was also involved with the National Parks combat tracker teams, summed up the action shooting sports pretty well – “They’re all we have and they’re better than nothing.”

On duty in the early days I always fed my .45 with factory ammunition – Speer’s 200gr jacketed hollowpoints, and in later years going for 230gr hollowpoints from Winchester or Hydra-Shok – and it lived, cocked and locked, in a leather inside-the-waistband holster custom-made by one of our local leathersmiths Tony Weeks.

Tony was a competitive shooter (one of the innovators of Practical Pistol in the days when it still was practical) who was also a thinking man who truly understood what a practical holster has to do. Tony was an Air Rhodesia captain, who was the real originator of the Comstock scoring system now used in action shooting matches. He was a good friend of Colonel Jeff Cooper’s – the colonel would stay with Tony when he visited Rhodesia – and much of Tony’s craft was probably shaped by Jeff Cooper’s philosophies – such as Cooper’s comment following the 1981 Practical Pistol world championships in South Africa that “To the extent that such a thing as a competition holster exists, the organizers of the competition have erred.” Tony was set in his ways. He wouldn’t hear of a thumb break or any other retention mechanism apart from making his holsters fit the gun properly. In order to get Tony to make me a right–handed model, I had to tell him it was for someone else. (I found it quicker to draw from a small-of-the-back holster with the left hand when the grip was presented to the left.) Yes, I know I swept myself every time I drew it, but I was never DQd by anyone I arrested! And a note here – never, ever, if you’re going to carry a 1911, as opposed to just use it on the range, mess with the grip safety. Even with a good holster, you will, from time to time, find your safety catch disengaged. A couple of spare magazines, in pouches, on the belt, and all was good.

In the end, I used this venerable tool to fire a few warning shots over the years, and once, when rapidly running out of options, brought it down on one miscreant’s skull. It served me well, and I wish I still had it.

And then I saw a compact 1911 made by Safari Arms. I had to have it! I realized Z$7,000 for my original investment of $500 on the Colt, and bought, what I soon came to (almost) affectionately call, my Safari Jams. (Lest I give the wrong impression of a company which made some very fine firearms, it was this particular piece which was a hoodoo, and I received prompt and courteous backup from Scheutzen Arms in the ‘States when I contacted them.) It had a compact slide fitted with a bull barrel and a full-length recoil spring guide. The ejection port was already modified, and there was a very robust set of LPA adjustable sights sitting on top. This particular slide assembly came from the factory atop a small, six-round frame. This pistol, however, had been fitted with the standard size seven-round frame. All was of stainless steel, and best of all, my ambidextrous safety and all my Pachmayr fittings dropped straight in. But it was never 100 percent reliable, and like a “mechanic’s car”, it was better off as a “gunsmith’s gun”.

I sold it to a very good friend and local gunsmith, Nigel Wentworth-Browne, and he solved all of its problems and it still shoots today with 100% reliability. Another good friend, Chris Pakenham, a former National Parks warden, now owns that pistol.

I then bought a Glock. The model 21 in .45 was for me. The trigger took some getting used to, but not only did it work every time, it held 16 rounds of .45 ammo (with the +2 magazine bases I fitted), and a round in the chamber. (No, it won’t go off by itself – it has a firing pin block.)

OK, I had to play around just a little, but there aren’t many parts on a Glock to customize. I dropped in a titanium firing pin, and put in the light connector to improve the trigger pull. I also fitted a nice set of iron sights, and I was happy. The only design flaw in the Glock, in my opinion, is the leaf spring for the magazine release, which cannot be trimmed to reduce tension. To correct this I had an extended mag release made out of aluminium, but it is still not wholly to my liking. But I shot at the time maybe ten competition matches a year in Zimbabwe and South Africa, and I shot one world champs with it, and over the years it has only let me down once, when the arm on the trigger linkage which deactivates the firing pin block sheared off.

Clicks instead of bangs are not good. As a carry gun, it does need a very solid holster which adequately protects the trigger. I have had very good service from Fobus holsters. This is another example of how the “practical” shooting sports fall short for training – this mode of carry is now prohibited in the rule books for most divisions, but is in fact one of the most practical real-world methods of carrying a handgun, especially in a vehicle.

In 2006 I “upgraded” to a Glock 22 in .40 S&W (smaller frame, more ammo capacity) and I carried it on duty and shot another world champs with it, as well as the southern African circuit. And now? After having sold the Glock and built up a Colt MKIV S70 .45, with which I won the Zimbabwe IPSC Classic Division National Championships – I have more or less retired from competitive shooting. So I’ve built another steel-framed .45 Commander for carry while takin’ care of business. For me, the circle is complete – at least back to Bophuthatswana days.

Charlie Haley, who, having left the police after twenty-two years and was an accomplished gun writer and competitive shooter himself, got me thinking when he postulated starting a regular backup/hideout gun shoot. Because, the one over-riding rule about carrying a firearm, is that you need to put in as much practice as you can with it. The sales receipt does not confer any skill or acumen.

Some words on backup guns – always have two handguns if you think you might actually need one (something else precluded by “practical” pistol rules). And in certain circumstances where concealment may become a trouble along the way, the primary gun can be hidden away in the vehicle and the smaller backup gun carried less obtrusively. I have had two personal preferences over the years. Obviously, ammo compatibility being a consideration, another .45 is one logical choice. There are a number of fine li’l baby .45’s out there, but we are pretty limited in terms of what’s available in deepest, darkest Africa.

My choice was therefore the .38 Special revolver. I have had two good ones. For years I carried the Colt Cobra, an alloy frame gun which was well-made, reliable, and hideable anywhere. Unlike many of its counterparts, it sports a 6-round cylinder instead of a 5. It was followed by a little Smith & Wesson Model 38 Airweight Bodyguard that I was given by Charlie as a Christmas present one year – brilliantly fast to draw and fire.

Do not bother with a backup gun if you aren’t going to carry spare ammunition for it. Again, the photographer’s vest (now, after 9-11, Afghanistan and Iraq I suppose we should call it the contractor’s vest) is the way forward, with enough pockets for the second gun and its magazines or speedloaders.

Ammo is another consideration. Your pistol may feed anything reliably on the range – but will it feed the state-of-the-art hollow-point ammo you carry in it? Reliability is a far more important consideration than the merits of all the “magic bullets” that have ever been devised. That and being proficient enough to hit what you’re aiming at, under stress. So at the end of the day, do you choose to carry a 2” .38 Special or a .45ACP? Do you spend your hard-earned cash on Winchester SXTs or Speer Gold Dots or Federal Hydra-Shocks? Clearly, none of those choices matter nearly as much as how much money you spend on your practice ammo, and how much range time you put in, in order to become truly proficient. As for me, I’ll stick with my .45ACP. If for some reason I’m wrong now, then I’ve been wrong for the last forty years, so why spoil a good thing?

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!