There is something very special about the Zambezi Valley, no matter the time of year or the reason for the visit. And one of the most special places in the Lower Zambezi is the Rifa Education Camp.

Rifa as a concept dates from 1982, when the Zimbabwe Hunters’ Association, founded in 1949, built the inaugural education camp at Nymomba, where the mighty Zambezi exits the Kariba Gorge; but the site was not as easily accessible as it should have been to facilitate the likes of school busses and two wheel-drive vehicles. Five years later, in 1987 the present camp was officially opened, with students from Sanyati High School in residence – and for over thirty years, set against a backdrop of acacia trees, wild figs and tamarinds, it has provided a unique wilderness educational experience for youngsters from all over Zimbabwe.

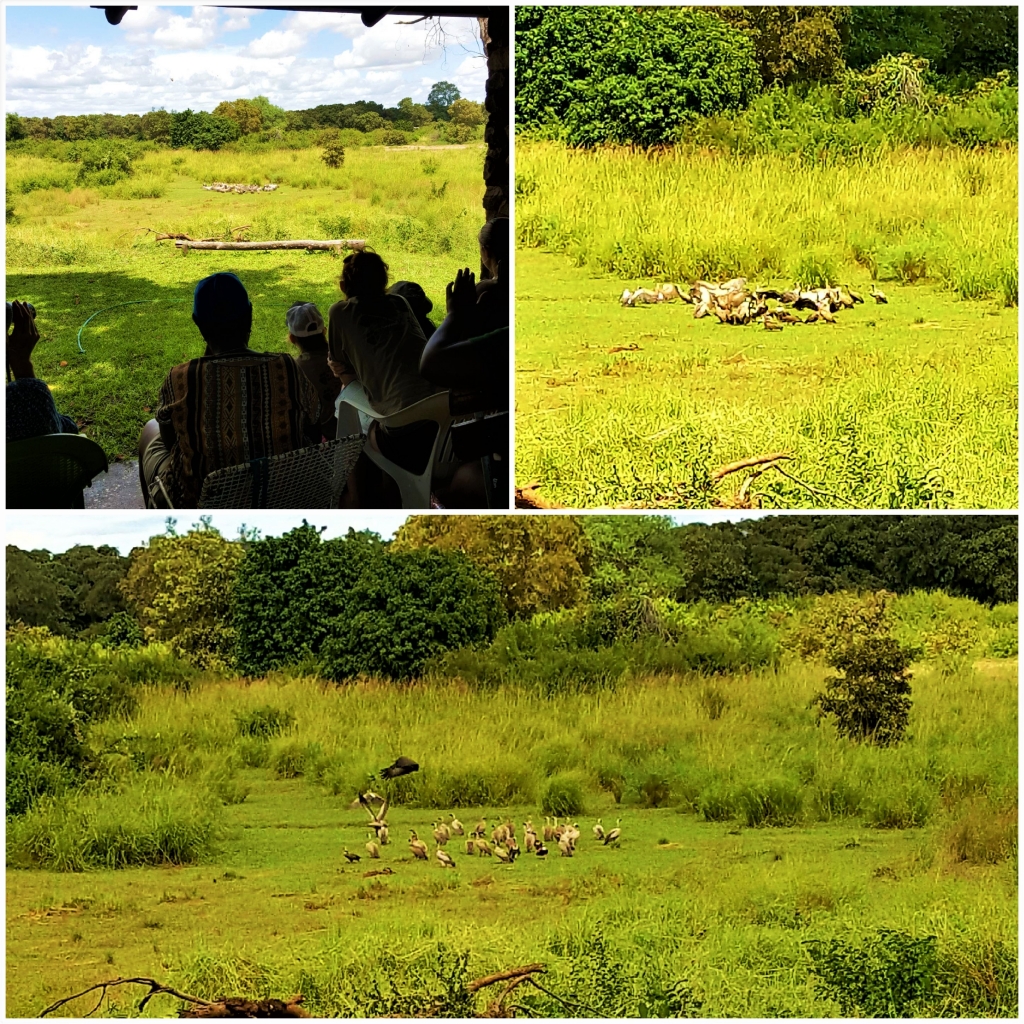

In earlier days, before the creation of the Kariba Dam and the subsequent siltation and formation of the wide flood plain below the Kariba Gorge, the Zambezi would have flowed past the present-day site of Rifa; today, the mini-floodplain that separates the camp from the river serves a number of educational purposes, such as housing the camp’s famed “vulture restaurant”.

All throughout the year, even during holiday periods, groups of learners numbering from a dozen to two or three times that number will arrive on a Sunday afternoon, and participate in a week-long series of activities designed to establish a bond with their natural history heritage through practical, hands-on experiences. And it is well worth always keeping in mind that this opportunity always has been and still is made available through the Zimbabwe Hunters’ Association – just so we don’t forget who really pays for most of the hands-on conservation education in Africa.

Not to be confused with Zimbabwe’s Professional Hunters’ and Guides’ Association, the Zimbabwe Hunters’ Association was formed as the umbrella organisation for the country’s non-professional, recreational, citizen hunters just under seventy years ago. And while the ZHA thrived up until Zimbabwe’s land reform exercise at the start of the new millennium, after that opportunities for citizen hunters dwindled dramatically. Most of the private land which had previously provided affordable hunting for everyman was re-allocated and very little thought was given to the long-term preservation of wildlife. This meant that citizen hunting opportunities then reverted to being mostly hunting camps, booked through National Parks, and which came with a higher price tag – too high for many.

Throughout all of this turmoil, the Zimbabwe Hunters’ Association – and Rifa Education Camp – have survived. In addition to the overall guiding hand of the ZHA, a sign on one of the dormitories proclaims that the block was refurbished with the assistance of the Dallas Safari Club in the United States. In this day and age, with an uninformed news media blindly vilifying sport hunting at the urging of various animal rights activist groups, Rifa serves as a reminder of the hunter’s ultimate role: that of conservationist. First World animal rightists are notoriously like a T Rex in baggy trousers when it comes to reaching for their wallets to fund anything practical like Rifa.

The students’ experience in camp follows a structured but at the same time fluid curriculum, where knowledgeable staff members, such as ex-National Parks officer and professional hunter Dave Winhall, cover the practical aspects: tracking, stalking, hunting, skinning and dissection, while qualified teachers from whichever school is in camp at any given time provide formal lessons in subjects like Biology, Geography and conservation and ecology. In addition, the Zimbabwe Hunters’ Association compiles a roster of available volunteer lecturers who can augment the standard topics with their knowledge in specialised fields; they also provide extra security for the students when on walks and other excursions. One thing that is impressed from day one is that the camp is wholly unfenced and is located in an untamed wildlife area.

On my first visit to Rifa as a volunteer, I accompanied former CID detective superintendent Charles Haley who lectured at length on firearms and ballistics, along with practical demonstrations. As I work on my notes in camp on this visit, I am with former National Parks warden Chris Pakenham, who just held a very successful group discussion on practical conservation and law enforcement this morning. Of the thirteen high school students in camp this week from Harare, two have never been to the bush before and two are visiting Rifa for the second time. It’s a pretty mixed bunch, and the whole idea is to provide a memorable and enjoyable experience that will not only get them thinking about wildlife and conservation in general, but also current topical issues like sport hunting, habitat degradation and loss, human:animal context from the perspective of a rural villager, and Zimbabwe’s three-decade old shoot-on-sight option for anti-poaching patrols.

Rifa comprises, first and foremost, the mighty Zambezi; the camp itself is nestled at the base of a rugged amphitheatre of volcanic cliffs, and the floodplain is home to mopani forests, fig trees, acacias, and a wide variety of ungulates together with the species which prey upon them such as lion, hyaena, and African painted dog. A truly imposing crocodile has taken up residence near the bream pools, and Freedom is almost on a first name basis with the black mamba that lives a little ways above the pools. Resident hippos keep the lawn in check, and it is not uncommon to see a genet peering out from behind a tree as you make your way to the dining facility after dark. The loud, rumbling exclamations from the lions pierce the night, when the buffalo herds are close enough, and virtually every night spotted hyaena announce their presence on the camp’s periphery . Rifa is Africa at its best.

Students and visitors are housed in three separate dormitories, accommodating up to thirty individuals, and there are four rooms for school staff and attending volunteers.

Day one commences with an early awakening, which is followed by a comprehensive safety lecture; it is important to remember that for many of the students this is their first exposure to the bush. In addition to Dave, the students will be accompanied when in the bush by one or two volunteers from the Hunters’ Association and a National Parks ranger, most armed with heavy calibre rifles.

The group will then take an early morning walk out of camp, while Dave readings what he calls the “Rifa morning papers” to the learners – the Granite Gazette and the Silicon Times. These comprise all manner of signs left behind from the previous night, and the “headlines” often pertain to the comings and goings of elephant, lion, leopard and buffalo. The tracks are not only identified, but interpreted to give a clear picture of what probably transpired around the camp the night before. Dave explains the “Four Ss” of tracking – shape, shine, sun and shadow – to the students, for most of whom reading sign is more like an occult art than a science. Porcupine, genet, hyaena, squirrel, mongoose, and the odd snake spoor are among the myriad other signs to be found on a typical morning. The vegetation provides an ever-changing backdrop, too, depending on the time of year – from the shaving brush-like flowers of Combretum mossambicense toward the end of the dry season to the boababs in full leaf.

On other days, students may be guided to the Chipandaure River which flows beneath rugged cliffs suffused with bee-eater nests, or to Long Pan. They may trek up Shumba Hill, where they can see the difference between the controlled conservation area directly below them and the effects of man’s depredations – stream bank agriculture, deforestation and soil erosion – on the opposite bank of the Zambezi. They may be taken to naturally-occurring hot springs, or to Sunset Point on the banks of the Zambezi which boasts some of the most glorious sunsets imaginable, over Zambia.

Lessons may include river bank erosion, or conducting practical experiments in river flow rate, or transect sampling. Secluded but teeming with wildlife is Arinatious Pan in the heart of Rifa – though elephant cow herds and buffalo don’t always allow trespassers into this hidden area.

Rifa has its own National Parks hunting quota, and during the weeks when students are present an impala is hunted. It is professionally dissected and the learners see the inner workings of a ruminant’s digestive system, the heart and lungs in the thoracic cavity, and the structure and musculature of the limbs. Most students have never tasted venison, and they will have the opportunity that evening. Whatever remains of the animal is laid out at the camp’s “vulture restaurant”, and the learners can watch from a few metres away as Hooded, White-backed and Lappet-faced vultures, sometimes numbering over one hundred, come to the feast. That evening, hyaena and the occasional lion may come in to have a look. Late afternoon or early evening walks are conducted to round off each day.

As a result of generous donations, Rifa has a library, a laboratory and a small museum, and during the heat of the day these are open to the students.

Programmes like the one at Rifa are essential if we wish to inculcate in the next generation the basic cornerstones of conservation; if they are made available by the hunting fraternity, it is the best way I can think of to demonstrate the unbreakable bond between sport hunting and conservation.

During the course of a year, as many as a thousand students may pass through Rifa, from both the country’s urban and rural areas. In addition, the camp is made available, when space allows, to local natural history groups like Birdlife Zimbabwe; the Zimbabwe Professional Hunters’ and Guides’ Association occasionally conducts training exercises there.

Although fees are levied by the Hunters’ Association for the use of the camp, the real cost is moderated, as it would be unaffordable for most schools. Many of the schools attending are from disadvantaged backgrounds, and the ZHA heavily subsidises the programmes at Rifa to provide a unique educational experience to those who would otherwise not be able to afford it. It is only by doing this that we can impress on them the need for conservation at all.

As with all other things, it is our generation’s responsibility to educate the next generation on the importance of their natural history heritage. The Zimbabwe Hunters’ Association, through its Rifa Education Camp, has been providing this education for the past thirty five years and with the help of the hunting community worldwide can continue to do so for generations to come.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!