I J Larivers

Unique to the 21st century, with the phenomenon of social media, is that a person can acquire an army of “followers” pretty much without having done much of anything at all. I’m not putting this down, because it usually harms no one and broadens everyone’s horizons. But perhaps it’s time to reflect on those who have gone before. Back to the day when a flight to Africa took four days, including overnight stops, on a Short Solent flying boat – if it got there at all.

Most of us are familiar with the account of Ernest Hemingway’s near miraculous survival after two successive plane crashes in Africa in 1954. We know the story of Teddy Roosevelt’s 1909-1910 safari to East Africa, outfitted by the Smithsonian Institution. Who hasn’t heard of Amelia Earhart? No doubt these folks were at the forefront of adventure in the last century. But one thing that never ceases to amaze me is how many adventurers from that era most of us have never heard of, or perhaps have forgotten.

Very few people are probably aware that Trader Horn was real, too, but he was. His real name was Alfred Aloysius Smith, and he was an ivory trader with Hatton & Cookson’s in what is now Gabon in the latter 19th century – and if you like this sort of thing, ‘Tramp Royal’, a study of his life by Tim Couzens is well worth seeking out. It is a reminder that there have undoubtedly been so many great adventures, the stories of which have never been told and now never will be. That frustrates me.

Just the other day, I became aware for the first time of the existence of Osa and Martin Johnson. Fair enough, neither was still surviving on the auspicious day of my birth, but free from the e-burdens of today’s technology, I grew up reading books – and books about Hemingway and Roosevelt and the Johnsons were the kind of books I read. Martin and Osa Johnson had a lot in common with Richard Halliburton. They were professional travellers who were able to capture the public’s imagination with their exploits and thereby earn a good living from their films and books, like Martin’s ‘Over African Jungles’.

Kansas is almost synonymous with heartland in America, and both the Johnsons hailed from there; Martin grew up between Lincoln and Independence, and Osa Leighty was born and raised in Chanute, the town which is today the home of the Martin and Osa Johnson Safari Museum. This museum is primarily why the Johnsons’ memory and achievements live on.

The museum, which started out simply as the Safari Museum, was founded in 1961 with a core collection of the Johnsons’ books, photographs, films, and other related family memorabilia, with the intention of not only telling their story of adventure but also encouraging further research into the fields of wildlife and ethnology in Africa and the South Pacific. To any who think the technological terrors of the 21st century might have eclipsed the accomplishments of the Johnsons, the museum is very much alive and well; in 1998 it was named one of the “top ten historic sites for Valentine’s Day by the History Channel Traveler website, and in 2001 The Pitch, a weekly newspaper out of Kansas City, named Chanute and the museum as “Best Romantic Day Trip.”

Martin Johnson’s first recorded taste for adventure was when he signed on as a crewman and cook for Jack London’s voyage across the Pacific in the ‘Snark’.

That one I did know about, for I had read that book: In typical Jack London style, he acquired the skills of sailing before the mast and celestial navigation during the course of his voyage across the South Pacific in a 45-foot ketch he had built and named after Lewis Carroll’s famous poem; he passed these along to his readers in ‘The Cruise of the Snark’.

London, his wife Charmain and a small crew put out from San Francisco and sailed across to Hawaii and thence to the Marquesas, Tahiti, Bora Bora, Fiji, Samoa, and the Solomons before ending their voyage in Sydney, Australia. London’s engaging first-person accounts, like so much of the Johnsons’ later works, gave the public their first introduction to these exotic locales.

At the conclusion of the two-year excursion, Martin Johnson put together a travelling roadshow to highlight his photographs and souvenirs from the voyage; it was while visiting Chanute that me met Osa Leighty.

Osa was only sixteen at the time, ten years younger than Martin, and in the beginning she found his tales of far-off adventure and photos of cannibals somewhat disquieting. It would be an understatement to say Osa’s father was enthralled with the young adventurer either, or the relationship that quickly developed between the two; after a three week courtship they were married in May of 1910.

Their first major adventure together was in 1917, when they embarked on a nine-month voyage through the New Hebrides and Solomon Islands. While visiting a tribe known as the Big Nambas – which really identifies the language spoken by a group of people still living in modern day Malekula, Vanuatu – they were held captive by the chief and only allowed to continue on their way after the intercession of a British gunboat facilitated their escape. There were decided advantages to travelling the world in the days of colonialism! The following year, their film footage was used to create the feature film, ‘Among the Cannibal Isles of the South Seas’.

After they had returned home from one of their epic expeditions, the Johnsons would edit their footage and embark on lecture tours describing their adventures and showing their unique films. Although the facets of south seas life and African wildlife which they could capture on film were limited by the technology of the day, and neither Martin nor Osa had any formal training as naturalists, their footage was extremely valuable because they went out of their way to avoid material that was staged and a lot of what they were able to film was cutting edge stuff because it had never been seen or captured on camera before.

In 1919, Martin and Osa returned to Malekula – but this time with an armed escort – and again collected film footage and artifacts from the Big Nambas. As it turned out, ‘Among the Cannibal Isles of the South Seas’ had come to even that remote corner of the earth, and said cannibals were suitably placated by their new movie star status and this time around, they were eminently accommodating.

Following their trip in 1920, visiting British North Borneo, and sailing up the east coast of Africa, two films followed in rapid succession – ‘Jungle Adventures’ in 1921, and ‘Headhunters of the South Seas’ the following year.

While the titles conjured visions of adventure on the high seas and perhaps a large dose of melodrama, for many folks this was their first exposure to these far-off lands and no one can argue that they were the fore-runners of today’s Discovery and National Geographic channels. It was perhaps inevitable that after their voyage up the east coast of Africa the Johnsons would turn their focus to the Dark Continent.

In 1923, they released the feature film, ‘Trailing Wild African Animals’, which was the result of a 1921-1922 expedition, and they embarked on an epic journey from 1924 to 1927 during which they got a wealth of material from a remote area in northern Kenya close by Mt Marsabit. Returning to the United States with a trove of film footage, they brought out Martin’s ‘Safari and Simba: King of the Beasts’ in 1928. Thirteen years later, in 1941, film and experiences from that expedition was used to make ‘Four Years in Paradise’ – Paradise being their name for the small lake they had camped beside.

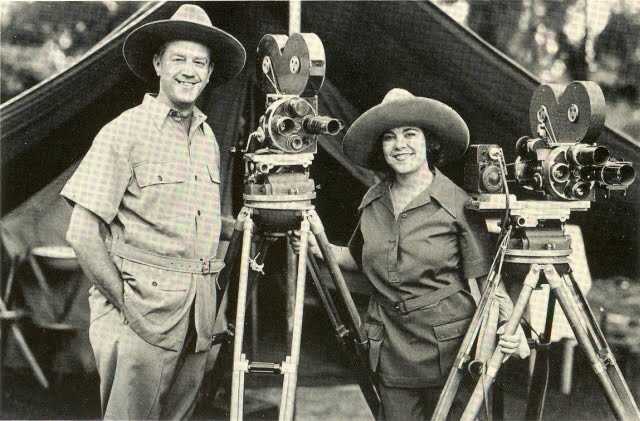

Although at first she had been a bemused and somewhat hesitant adventuress, Osa Johnson quickly developed a flair for her newfound career, taking charge of the logistics and staff on Johnson expeditions, and helping out – very capably

– behind the camera. In camp, she procured the supplies, planned the meals, and was no mean hand with a rod and a gun, thus ensuring that there were always fresh provisions. Although it would be extremely un-PC today, once when a rhinoceros charged Martin, Osa lifted her rifle and dropped the enraged beast in its tracks; as a result, Martin was able to capture all the action on film.

During the years 1927 and 1928, Martin and Osa Johnson made their third African safari, this time along the Nile in the company of George Eastman, best known as one half of the Eastman Kodak company. When it came out in 1930, ‘Across the World with Mr and Mrs Johnson’ was one of the first ever talking picture documentaries, with Martin Johnson supplying the narrative.

In 1978, Colonel John Blashford-Snell and HRH Prince Charles launched Operation Drake – sort of an Outward Bound concept on board tall ships circumnavigating the globe, with the goal being to use adventure, exploration and community service to develop self-confidence and leadership traits in young adventurers. Operation Drake was followed in 1984 by Operation Raleigh, and it was so outstandingly successful that it morphed into Raleigh International in 1992. Today it is recognised as the world’s most ambitious sustainable development charity, working in remote areas to assist locals in managing their natural resources. But Martin and Osa Johnson had the idea back in 1928.

That was the year they selected three Eagle Scouts to accompany them on safari in East Africa. From a promotional standpoint it was pure genius – national competition and all to select the lucky winners – but it was also good, solid leadership training for the youngsters. The trio co-authored ‘Three Boy Scouts in Africa’ (1928), and Robert Douglas went on to pursue a successful career as an attorney, David Martin became an executive in the Boy Scout movement, and Douglas Oliver ended his career as an emeritus professor of anthropology at Harvard University. The opportunities for adventure they had with the Johnsons couldn’t have hurt.

Thirty years ago I went to see an okapi in the Ituri forest in what was then Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Truth be told, at that time I was really following the battle honours of Col “Mad Mike” Hoare’s 5 Commando, but who wouldn’t take a detour to see an okapi, with a few Mbuti pygmies thrown in for good measure? I spent several days at the station at Epulu and spent time with both. In much the same way that the Nile today must be much the same as when Sir Samuel Baker saw it, I don’t think things had changed much since the Johnsons had filmed in the Congo half a century before. The Johnsons brought out ‘Congorilla’ in 1932 – the first wildlife “talkie” whose sound track had actually been recorded in Africa. (For trivia buffs, ‘Trader Horn’, which was released the year before was the first non- documentary film ever shot on location in Africa, so this was all pretty innovative stuff.) The film even spawned a dance – the Congorilla Foxtrot – which was resurrected at least once by the Cairo Club Orchestra in Melborne, Australia!

The Safari Museum isn’t the only thing in Chanute to bear the Johnsons’ name – so, too, does the Chanute Martin Johnson Airport. Five years after Lindbergh flew the Atlantic in the Spirit of St Louis and five years before Amelia Earhart disappeared over the Pacific, Martin and Osa Johnson learned to fly – at that airport. Once they were licensed, they bought a couple of Sikorsky amphibians, an S-39 they named Spirit of Africa, and an S-38, Osa’s Ark. Coincidentally, the same year the Johnsons got their pilots’ licenses, Richard Halliburton’s bestseller, ‘The Flying Carpet’, which was the story of his circumnavigation of the globe in an open-cockpit Stearman 3C-B, hit the shelves.

Martin and Osa’s fifth African expedition was airborne. From 1933 to 1934, they flew the length of the Dark Continent; their aerial film footage, including the first filmed over-flys of Mt Kilmanjaro and Mt Kenya, was both groundbreaking and outstanding. Never again will anyone, anywhere in Africa, see, let alone film, the vast herds of elephants and other game they saw below them. ‘Baboona’ was not only the inevitable feature film that was born of this expedition, but on 3 January 1935, it became the first ever in-flight move, being shown on an Eastern Airlines commercial flight.

The Johnsons’ last expedition was again to their old stomping grounds, British North Borneo, where they filmed ‘Borneo’ between 1935 and 1936.

Western Air Express Flight 7 was a twin-engine Boeing 247D operating as a domestic scheduled passenger flight from Salt Lake City, Utah to Burbank, California on 12 January 1937. In severely limited visibility resulting from heavy rain and fog, the Boeing had wandered off course on its approach into the Union Air Terminal at Burbank. When the captain, William Lewis, suddenly saw high ground ahead, he cut power to reduce the force of the impact and “pancaked” into the hillside. It crashed shortly after 11.00 near Newhall, California. There were three crew members and ten passengers aboard. Martin Johnson died from injuries received in the crash and Osa was seriously injured.

Clark H Getts had been the agent managing the Johnsons’ lecture tours, and took over Osa’s financial affairs following the crash; by August, he had become the new man in her life. It was Getts who got Osa signed on as a consultant for the Darryl F Zanuck film, ‘Stanley and Livingstone’. Getts artfully sculpted Osa into a more glamorous figure, who was even voted one of the best-dressed women in America.

Osa was very capable at a good many things, but she did hire a ghost writer, Winifred Dunn, to help her pen her autobiography, ‘I Married Adventure’, which went on the shelves in May of 1940. It was the year’s best-selling non- fiction book. The film version, by the same name, premiered in August. (Osa had also drafted another manuscript about their Borneo trips, which was published posthumously as ‘Last Adventure’ in 1966, with the aid of Pascal Imperato.)

Osa Johnson and Clark Getts married secretly in April of 1940, and followed that up with a public wedding in February of the next year.

Osa had had a problem with alcohol – following Martin’s death – and while Getts was busy keeping the wheels of the Johnson machine turning with re-worked footage and some new material, Osa started drinking again. Getts had her put into a psychiatric hospital in 1944, and a divorce in 1949 followed a bitter legal battle. Kelly Enright, in ‘Osa and Martin: For the Love of Adventure’, does a good job of quantifying what Osa was going through. Despite her disastrous relationships following Martin’s death, she was not some depressed alcoholic, but she had lost the man who had shared and shaped her life since the age of sixteen, and in many ways, it was a loss she would never be able to come to terms with. It is perhaps telling that one of the legal provisions of the divorce was that she was able to resume the name Johnson.

By 1951, Osa was not in good health; reminiscent of Clark Getts, who knew a good thing when he saw one, Osa’s lawyer John Crane moved in with her, but the end was near. On 7 January, 1953, plagued by coronary artery disease and financial difficulties, Osa suffered a fatal heart attack, aged 58. She had been planning a return to Africa.

The Johnsons were a high profile, very public couple, with a carefully-crafted image, but like all of us, they were also people with their own personal lives apart from that. Professor Pascal Imperato and his wife took the time to delve into who Martin and Osa Johnson really were. As he says in his insightful biography, the definitive story of their lives. ‘They Married Adventure: the Wandering Lives of Martin and Osa Johnson’, “What emerged were two people quite different in many ways from the public images they had created for themselves. We were not disappointed by what we found because even in their private lives, Martin and Osa had the power to inspire”.

Whatever one may say about the early 20th century quality of the Johnsons’ films, or the fact that they were not qualified natural historians their innovative contribution to the wildlife documentary genre is unquestionable. At the end of the day, Osa and Martin produced eight feature movies and published nine books. Osa was also the author of a number of children’s books. Despite her later relationships, she and Martin, who never failed to acknowledge Osa’s contributions, were clearly partners in every sense. The intrepid writer and broadcaster, known as the man who made Lawrence of Arabia famous, Lowell Thomas wrote of them, “It was a rare team they made, this partnership between two handsome people from Kansas. Indeed in the annals of travel and exploration, they were unique”.

Today, the Martin and Osa Johnson Safari Museum is administered by a twelve-member volunteer Board of Trustees, and is affiliated to two sister museums, the Musée de Manega, which is located in Burkina Faso, and the Sabah Museum in Malaysia, and it stands as a rare window into a world a lot of folks like me wish we could still step into.

Not forgotten into the 21st century, in April of 2001 Disney’s Animal Kingdom Lodge opened and featured an exhibit of Johnson photos and Osa’s book. American Eagle Outfitters used the Johnsons as the icons for its 28 franchised Martin + Osa clothing stores and accompanying Martin + Osa line of primarily denim classic and contemporary clothing. Sadly, the venture failed in 2010, but judging by the number of folks looking online, it’s not forgotten. The Johnsons’ photos continue to appear in the backgrounds of modern movies, like 2004’s ‘Lemony Snicket’s A Series of Unfortunate Events’, and ‘Night at the Museum’ from 2006.

Martin Johnson was once quoted as saying, “If ever a man needed a partner in his chosen profession, it has been I. And if ever a wife were a partner to a man, it is Osa Johnson”. The Johnsons shared twenty seven action-packed years together, and left behind a legacy that was unique and iconic of an era that is no more and will never be again. Their story is a glimpse into beginnings – basically the wildlife documentary as we know it – and endings – when the world was whole and there was so much left to see and discover. It is fitting that this story and these two rare individuals not be forgotten.

THE GUNS OF MARTIN AND OSA JOHNSON

During their four years by “Lake Paradise” in northern Kenya on the Ethiopian border, the Johnsons possessed quite an arsenal.

By way of heavy dangerous game rifles, they had three .470 NE doubles by Thomas Bland & Sons of London, a .505 Rigby bolt action rifle and two Jeffery .404 Mauser actions. As was done back in the day, when you were on prolonged safari, you ensured against breakages and malfunctions with numbers.

They also carried a Thomas Bland .275 with a Mannlicher action, and three .405 Winchester lever actions. The .405WCF remains to this day the most powerful rimmed cartridge designed for the lever guns, and was a personal favourite of Theodore Roosevelt on safari in Africa. And lastly, a Winchester Model 1895 in .32.

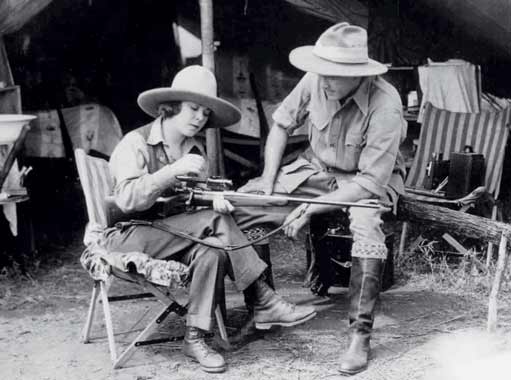

Also recorded is an American Springfield, also in “Mauser” action which they list as being a .303. I thought that this must be a typographical error, because of the manufacturer and the calibre, and in one very good photo Osa is shown with what looks very much like a Springfield sporter, possibly made by Griffin & Howe because of the side-mounted scope, so I’m going to say the Springfield would have been a .30-06.

They took along a Winchester repeating 12-gauge, a 12-gauge Parker double barreled shotgun, and two 20-gauge Ithacas, one sawn off.

Handguns were a pair of Colt revolvers – one a .38 and the other a .45. There is also a glamour shot of Osa with a Mauser Type A in 9.3x62mm; the Johnsons were known to pack in crates of ammunition, as was the norm back then, but a 9.3×62 would make a lot of sense in Africa where calibres like .30-06 weren’t as common. The one example that has seen the light of day and can be directly linked with Osa is an Oberndorf sporter, serial number 105930. It’s consecutive serial-numbered companion is known to have been sold through the firm of Charles A Heyer & Co of Nairobi, and as both rifles are identical down to the rubber buttplate fitted for a lady, one can surmise that both rifles were at one time owned by Osa. These sporters are known as among the finest of the Mausers.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!