Arguably much less well-known – in some circles – than James Brooke, the White Rajah of Sarawak, John Harrison Clark, King of the Senga, was nonetheless a force to be reckoned with in southern Zambia at the end of the Nineteenth Century.

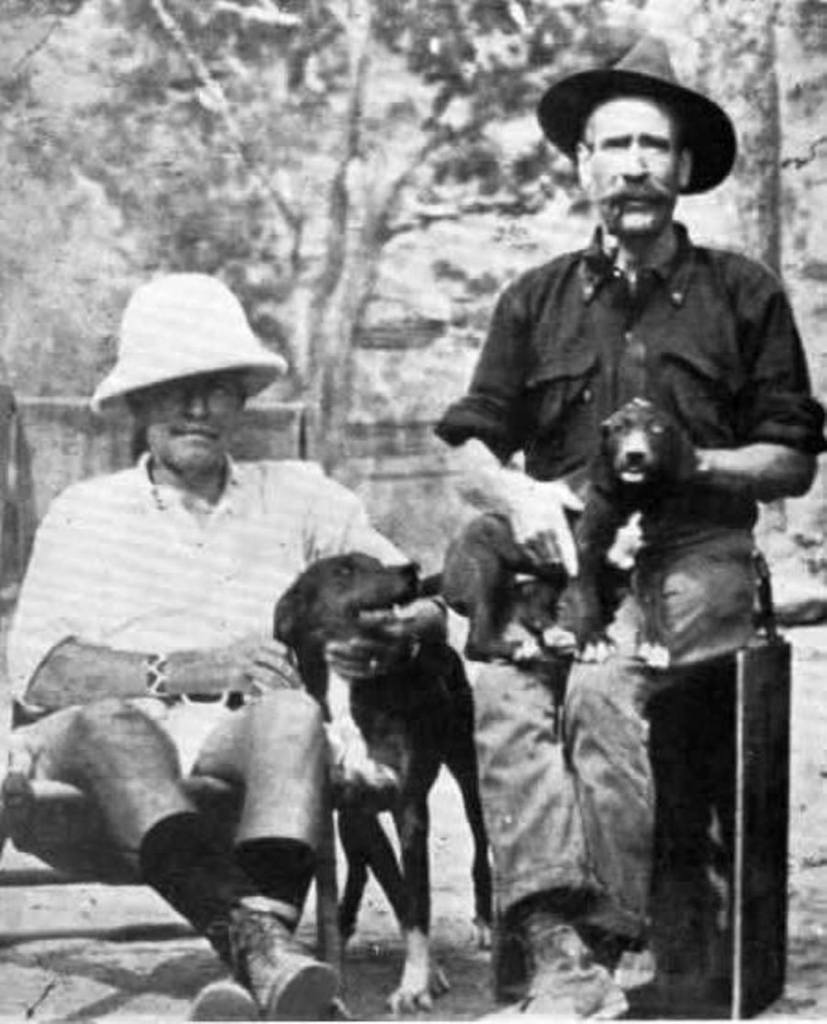

Clark was born in Port Elizabeth round about the year 1860, into a working class family. Growing up in the Cape Colony, he soon mastered the arts of marksmanship, horsemanship and bushcraft, and served for a time during the 1880s in the Cape Mounted Rifles. He was tall and physically imposing – well-suited to life in the bush.

But he wasn’t, perhaps, as well-suited to military discipline, and wanderlust soon took hold. It is not known exactly why he left the Cape in 1887. It may have been that he was simply in search of adventure, in a day when fences were closing in, and many of the great adventures were already the stuff of legend. Or perhaps he had to move on. One frequently-told story is that he was forced to flee the colony as an outlaw after having accidentally killed a man. Who knows? It was the time of legends, and he was the sort of character that would come to attract a mystique surrounding him. Whatever the reason, his wanderings took him to Portugese Mozambique, and he followed the Zambezi River upstream to the abandoned village of Feira, where the Luangwa joins the Zambezi. Now called Luangwa, and known to Livingstone, Feira had been founded by Portugese missionaries as probably the first European settlement in what is now Zambia, sometime around 1820. By1887, when Clark arrived, it was a ghost town. Deserted after a native uprising decades before, it had never been re-occupied. Its emptiness apparently suited Clark, and he took up residence, flying the British Merchant Navy’s red ensign above his boma.

Even as the Nineteenth Century was drawing to a close, the slave trade was still flourishing in Central Africa. Gangs of Arabs, Portuguese and half-castes preyed upon the people of the Baila and Batonga tribes. One of Clark’s first endeavours was to create and train a small “army” of sorts, comprised of the local Senga villagers. Shortly after, he assumed the mantle of chief – again it is not clear exactly how. One legend is that he arrived on the day the previous chief died. Another story is that he won his office by conquest, which is probably much nearer the mark. It is today generally assumed that he either defeated the reigning chief in battle, or that he liberated by force a Baila village where Portugese slavers were looking for wares. And so, “Chief Changa-Changa” came to be.

As he was the only one thereabouts with his own army, Clark levied and collected “taxes” in the form of cattle and other livestock from the African villagers and sold “trading licenses” to foreign merchants, reaping ivory, gold and other trade goods in payment. In the case of ivory hunters, his “export tax” was half of their bounty. Because he also defended the local villagers and colonial traders from slavers and marauders, he was able to get away with what would be today termed a protection racket, crowning himself King of the Senga into the bargain.

Oddly, this didn’t go down all that well with the Portugese authorities across the river in Zumbo. The path of least resistance was for everyone to get along, which they did for the most part, but on one occasion Clark invaded the Portuguese outpost, pulled down their flag and replaced it with the Union Jack, and then repaired across the river back to Feira, presumably to gloat. His point made, he made no attempt to prevent the Portugese officials from returning. Again, according to legend, he was once arrested by the Portugese, but had to be set free because the native troops refused to guard him, holding him in some awe. A little audacity goes a long way, and it seems that most folks were in awe of him at that time.

A king needs a queen, and Clark in due course married the daughter of the Chikunda chief Mpuka – though after the manner of the times, contemporary accounts have it that she was but one of many.

In 1895 the King of the Senga established a proprietary court to the north, building a new village in the fertile Luano Valley where the Lunsemfwa and Lukasashi rivers converge, and constructing a stone fort; he christened the new capitol Algoa, which was the Portugese name for his native Port Elizabeth.

As the old century drew to a close, Portugese influence in the region was waning, and Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa Company moved into the lands north of the Transvaal. The BSA Company had consolidated its hold over what they were beginning to call Rhodesia – now Zimbabwe – and Barotseland by 1894, and with Rhodes’ dream of a Cape to Cairo railway in mind, BSA Company explorers such as the legendary Frederick Russell Burnham looked to the lands north of the Zambezi and began to negotiate concessions with the more powerful local chiefs.

Major A G Deare set out from Fort Salisbury, how Harare, in 1896 on one such foray. His primary task was to meet with Chief Mpezeni of the Ngoni tribe, who co-existed to the east of Clark’s fiefdom. Hearing of Deare’s column’s engagement with Mpezeni, Clark sent a letter, signed “Changa-Changa, Chief of the Mashukulumbwe”, requesting a like meeting with the Major. In what in those days would have been much less of a coincidence than now, Major Deare – who had heard of the white king – discovered from his real name appended to the missive, that Clark was an old acquaintance of his from the Cape Colony, even having lived in the same town as he. History does not record whether the major accepted the invitation.

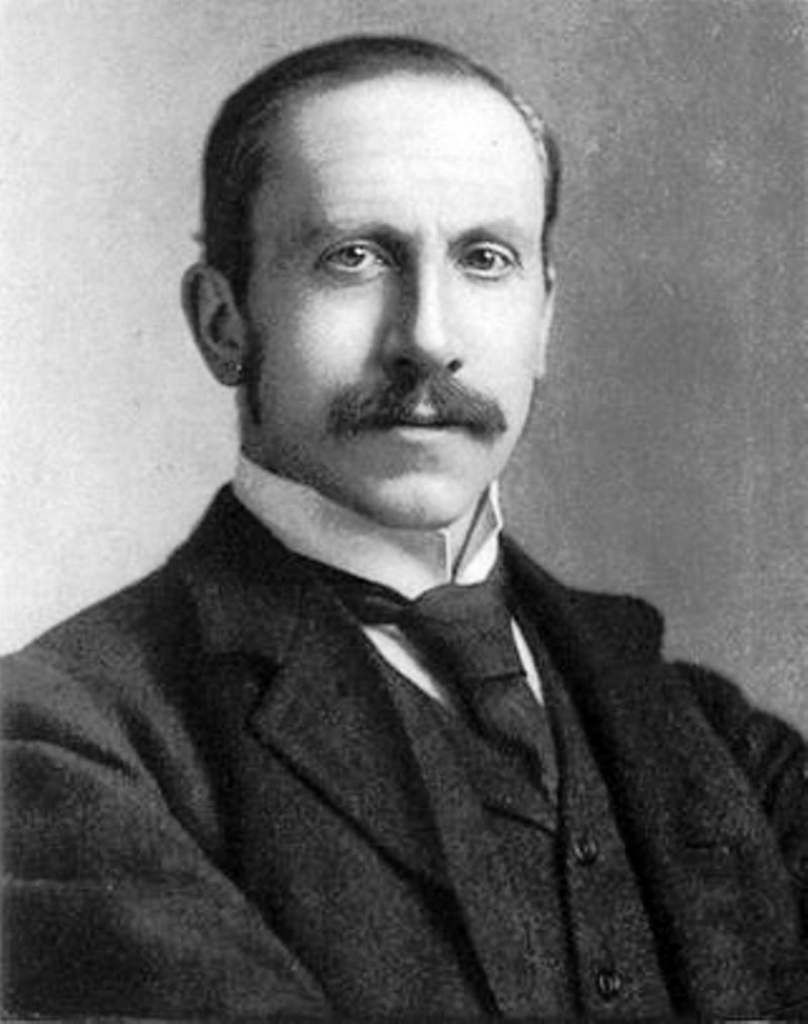

As was Earl Grey, the Administrator of the British South Africa Company in Clark’s time

But the writing was on the wall. Out with the old and in with the new. Clark had already acquired mining rights from two neighbouring potentates, and he used these to try and negotiate with the BSA Company’s administrator at Fort Salisbury, Earl Grey, so as to fall under the company’s protection. He pointed out the rich mineral deposits to be had. Chief Changa-Changa had good relations with the local tribes, and while the BSA Company had sent Lt Col Robert Warton north to represent its interests, Clark pointed out that, through him, Mashukulumbwe and Mpezeni would peacefully toe the company line. Clark still had his private army, which he claimed numbered between three and seven thousand. You don’t get a tea named after you for nothing, though, and Earl Grey’s response to Clark’s overtures was circumspect, bordering on arrogant.

Meanwhile, Clark continued quietly acquiring mineral concessions from chiefs Chetentaunga, Luvimbe, Sinkermeronga and Mubruma over the ensuing couple of years.

Clark also pointed out that he had negotiated labour agreements with the chiefs in the region, and contract labourers could be had for six-month contracts from among the neighbouring chiefdoms’ populations. He negotiated a monthly wage of ten shillings per man with the workers themselves, along with rations and accommodation, and proposed to Earl Grey that he could supply Salisbury and Bulawayo with all the manpower it might need, year-round if necessary, at £1 a head.

But John Clark’s relations with the natives weren’t as good as he liked to portray. He was known for a roving eye for the local womenfolk, which didn’t go down too well with the local menfolk, and in April of 1899, the BSA Company received a formal complaint from Chief Chintanda. Clark’s womanising was probably the real basis for discontent, but the chief also said that Clark had been representing himself as a BSA Company official and had been collecting taxes and levies, and negotiating concessions, under that auspices. How true that was is open to speculation, but it was certainly the type of story that Chintanda believed the BSA Company hierarchy would respond to. (Statements taken from other chiefs, such as Chief Mbruma also mentioned Clark styling himself a BSA Company agent, but made no mention of his sexual peccadillos. Many of Clark’s interactions with the local villagers are a matter of record, but it is hard to establish what he actually did tell them in order to get the concessions.)

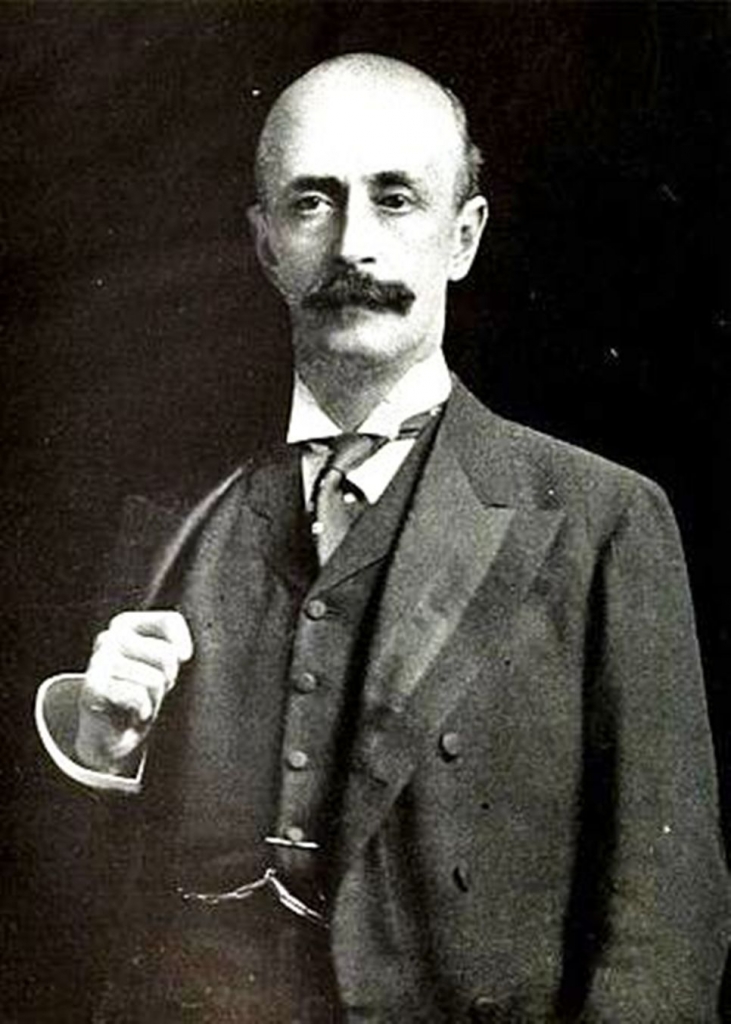

And respond the Company did, though probably less out of altruism and sympathy for Chief Chintanda’s grievances than concern that Clark was a threat to their empire-building in the region. Trouble was, Chief Changa-Changa’s domain was legally outside the BSA Company’s mandate. Company administrators were cautioned by their own attorneys that Rhodesian courts had no jurisdiction across the Zambezi at that time, and even after a formal application was made to no less a personage than The Right Honourable The Viscount Alfred Milner, Governor of the Cape Colony and High Commissioner for Southern Africa by Arthur Lawley, the BSA Company administrator in Matabeleland, that didn’t change. Lord Milner affirmed that he could not authorise legal or punitive action against John Clark by the BSA Company until such time as they held legal sway over the areas in question.

But Cape Town was a long way away, and the BSA Company was slowly but inexorably moving north. The Company’s own representatives were negotiating with the local rulers, and by 1900 the BSA Company had established a permanent presence to the northwest of Algoa, and had moved into Feira itself by 1902. This meant that Mashukulumbwe was now formally under Company control. How much legal weight Clark’s prior claims and concessions carried was a matter of conjecture. Though he tried to sell them to the Company, officially they would not entertain him, taking the stand that they were neither legal nor binding. It was now no longer about control of the region; Clark wisely wanted out.

The BSA Company, however did offer a buy-out in the form of compensation. Col Norman Earl-Spurr, who knew Clark in the 1920s maintained that the king was given farms as compensation, and this is backed up by William Brelsford, noted author of The Tribes of Zambia, as well as an informative piece in the Northern Rhodesia Journal entitled “Harrison Clark: King of Northern Rhodesia”. A M Bentley, offers a slightly different take, that Clark was offered land grants and mining concessions. Whatever the deal, Clark wisely accepted.

Hanging up his crown, Clark turned to farming. He had some success because he thought outside the box and tried crops that had not yet been grown in the region, such as cotton and rubber. Heavy rains destroyed an entire cotton crop one year, and sensing he was too old to deal with the vagaries of nature he repaired to Broken Hill, where he lived out the remainder of his life. His last formal employment was as personnel manager for a local mine, to which he was well-suited because of his good relations with the African population. Still affectionately known as Changa-Changa, he was active in community affairs, became a partner in Northern Rhodesia’s first commercial brewery and owned a Ford Model T – one of the first in the town.

I like to say that the only bad story is the one that’s never told. John Harrison Clark apparently did put pen to paper and drafted an autobiography, which would have been a compelling insight into his life and times, had it not perished in the fire which burned his house to the ground – and which he always maintained had been the work of the BSA Company because of their fears about what the eventual book might contain. William Brelsford held Clark in high regard, and that says a lot. When he died from heart disease on 9 December 1927, aged probably 67, he was a well-loved and much-respected member of his community.

“Changa-Changa” lives on in the local vernacular today, roughly translating as “boss”.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!