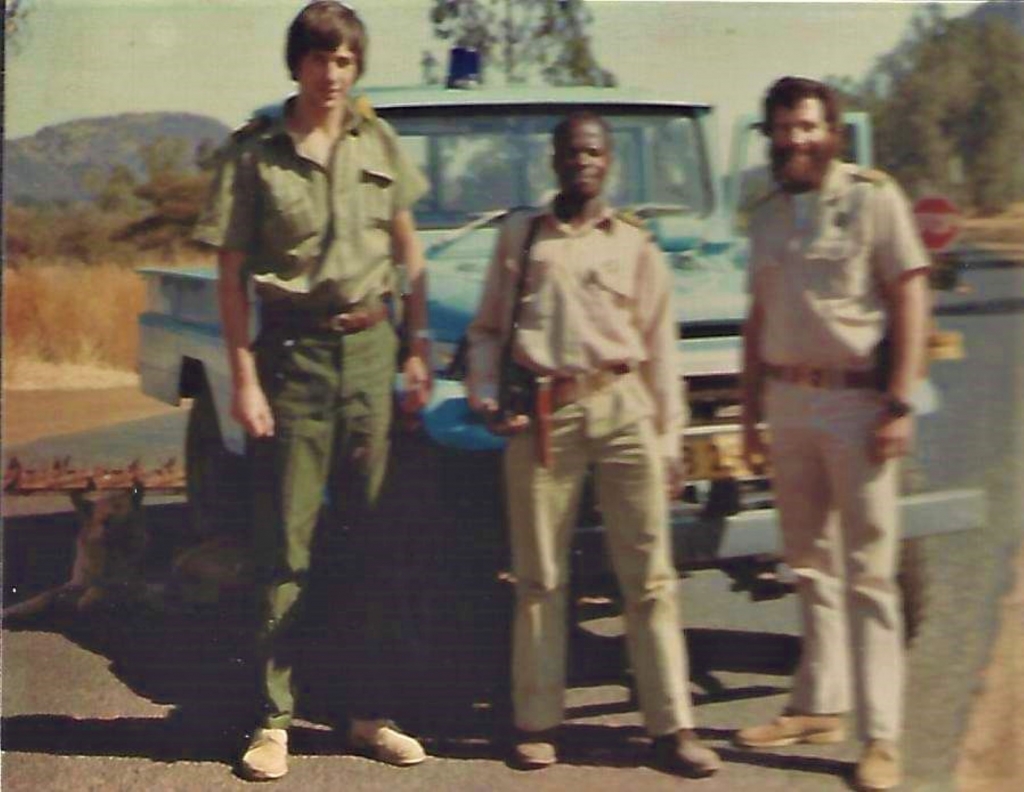

When Hans Koenig and I worked in Bophuthatswana, the resources were very basic. But eventually we managed to acquire a pool of vehicles, SSB radios and proper weapon systems instead of whatever was in the office safe, but it took time.

We never really managed to set up what I would consider as a great informer network. There wasn’t any major poaching cartel, with the majority of our “customers” being Afrikaans-speaking farmers. At first, we tried patrolling our districts. There were a number of bush camps where we could base ourselves – patrolling by night and getting as much sleep as we could throughout the day. I bought one of the old Lyman reloading kits and used to busy myself during the day bolting .45 rounds together. The large areas we had to cover made patrolling a very ineffective way of ever coming face to face with a poacher.

Our next strategy was OP’s on high vantage areas where we would be able to see vehicle movements after dark and work out whether or not they were on our turf. The big problem was that climbing up rusted ladders on water towers and suchlike in the dead of night was an excellent way to get killed, and using one or two vehicles and three or four personnel we still had to be able to intercept any vehicle that we saw spotlighting. Because of our meagre resources, this meant climbing down and doing it ourselves rather than having one person coordinating from the eyrie.

The only remaining solution was to erect roadblocks. In this vein we were fortunate. We had a good working relationship with our South African counterparts, but nature conservation officers in South Africa could not set up roadblocks without the approval and presence of the police (a significant number of whom were poachers themselves). Our laws put us on an equal footing with the police, and we operated autonomously. And rarely in conjunction with Transvaal Nature Conservation because of the logistics issues. Roadblocks had the disadvantage that they required trained manpower, but they could also be moved to several different locations during the course of a night, and therein lay their efficacy. There were ways around them in some places, but everyone at some stage had to use the highway.

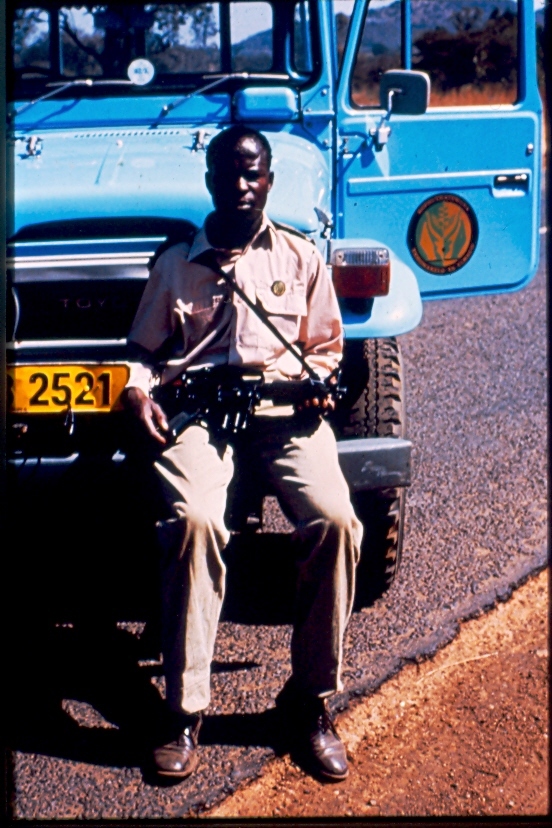

We got around the manpower issue by calling in officers from surrounding districts along with their game scouts for especially busy periods. I was particularly fortunate in my area because there were a number of young expatriates – civil engineers and the like – who were all too bored with the lack of diversions. We carried out training programmes and wound up with a cadre of willing and switched on reserve officers, and were able to operate in any districts anytime we wished.

Police roadblocks usually aim for high visibility, especially at night. We worked the other way around, hiding ours as best we could. Along a (usually quiet) road in the African bushveld at night, approaching vehicles announce themselves miles away – sound carries far and fast, and headlights are visible reflecting off the underside of power and phone lines long before they are seen on the road. By the same token, a roadblock is far from inconspicuous – flashing blue lights, headlights, and hazard lights, and myriad people moving around. Our tactic was to conceal the roadblock in a depression in the road or around a corner so as to minimize its signature. Safety was always a concern and we always left enough room for approaching vehicles to stop without slamming on breaks (the only fender-bender we ever had was in broad daylight). These were the days before cell phones, and we started making arrests.

We were not dealing with a particularly violent element, but anyone we would be interested in would be armed, so we made sure we had adequate manpower, and carefully worked out our arcs of fire and tactics. Every officer was in uniform and armed, and every vehicle had a blue light, whether mounted or Kojak-style, so there could be no doubt for someone driving up that we were there legitimately. We had portable road signs made that identified us (in the three requisite languages) as a nature conservation roadblock.

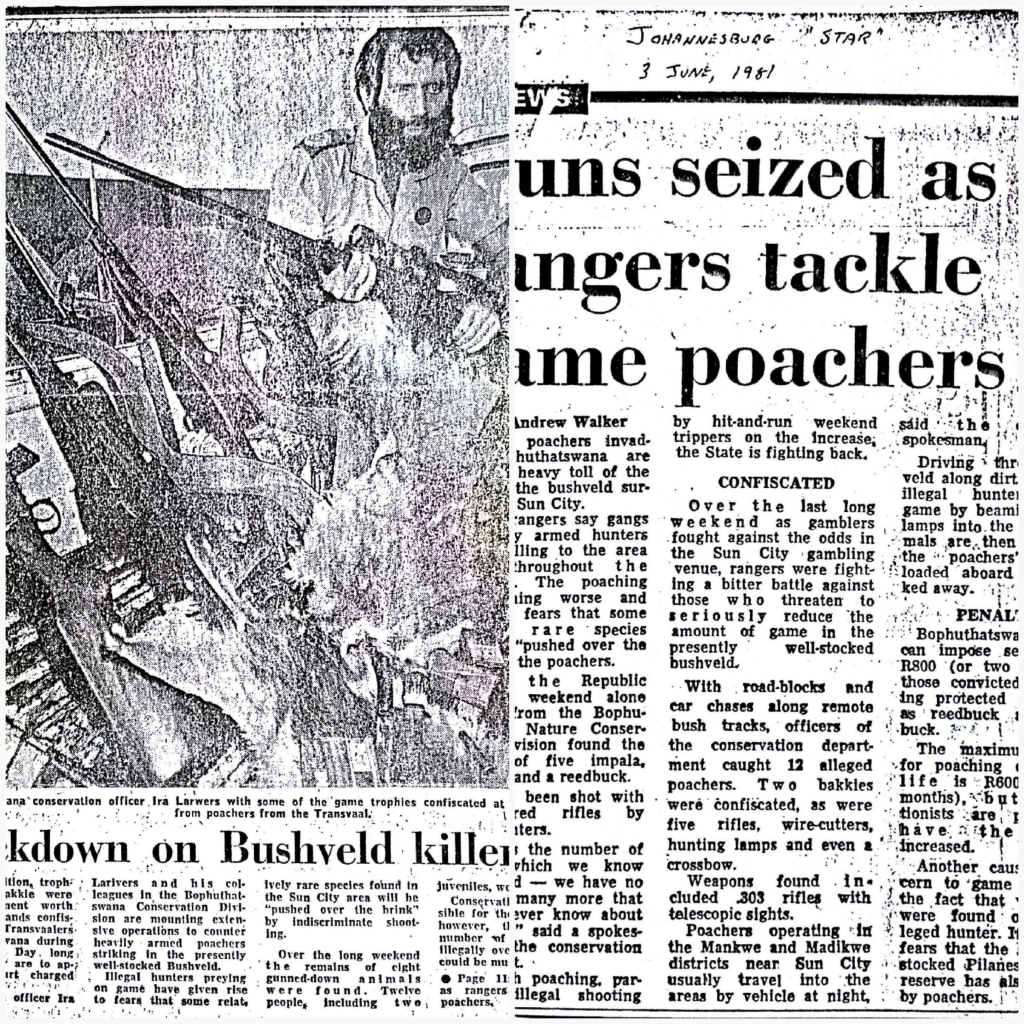

None of this had been done by our predecessors, so we were making it all up as we went along. Head office couldn’t have cared less what we did as long as it was within budget (which we eventually were given a hand in determining as well). I think it was only when we started arresting poachers and submitting reports to that effect, and even generated some media coverage that many in the capitol realized that we actually existed. Who are these guys, and why are they doing things? Where did they come from? That is the literal truth and no exaggeration, but we were making them look good, so all was well. (We would investigate the Minister of Defence for poaching from a helicopter and Hans would later catch the Assistant Secretary in our ministry diverting animals from a game capture operation to his farm in the northern Cape, but that was later.)

In our early stages, we found that some folks would have a go at running the roadblocks. Initially, we had a Ford pickup with a 3 litre engine that was extremely fast, and we could catch most such miscreants, and it livened up the evening – but we quickly learned not to place our roadblocks too close to the South African border, where we would have to break off the chase. We soon commissioned “Jaws”, a heavy steel rectangle that sported row upon row of jagged 3″ steel teeth – coincidentally, it was the width of one lane of traffic.

Roadblocks are tedium and monotony elevated to an art form. The majority of vehicles that pass through are law-abiding folk, or if not, most weren’t into anything that was of interest to us. A vehicle will perhaps slow down almost too soon, and if your hearing’s sharp you may detect the soft thud of a stolen starter motor or alternator landing in the ditch, and it can be amusing to take a stroll back up the road in both directions with a good flashlight when things are quiet to see what may be lying around.

Genuine poachers were also something of a grey area if we stopped them on their way out to shoot. The borders existing only on maps, even if they had the accoutrements it was impossible for us to say whether they were heading for a farm in South Africa or not. We had to follow the book, and the only things we could charge anyone for before they’d shot anything were possessing a firearm with a barrel length in excess of 20cm either in a loaded condition or outside of a gun case made for that purpose while on a public road.

In that vein, roadblocks are a good training ground for new officers and game scouts. People make mistakes and there is always an amount of discretionary leeway on the part of the conservation officer. This was something that we always battled to get across to our African scouts, and I don’t think we ever really succeeded. In Africa, authority equals power – it’s usually not seen as a tool to be used to achieve a legitimate objective. Once we stopped a truck towing a trailer. It was obvious the family had been in the bush, and so we asked to see inside the trailer. I found two rifles lying on a seat, in gun cases. Checking them against their licenses I found that one, a .22, was loaded with a full magazine.

My scouts were crestfallen when I cautioned the driver and sent him on his way – they wanted to arrest him – and his family – and charge them at the local cop shop. This would have been legally justifiable, but not the right thing to do. I asked my guys what the purpose of the cased and unloaded laws were – why carrying a rifle that way was illegal. They didn’t have a clue, never having even thought about it. I explained that those laws were in place to prevent someone driving along the road, seeing an animal, and quickly taking an opportunistic shot. After they accepted this, I asked them how likely they thought it would be that the guy, driving along and seeing an animal, would stop the car, rush back to the trailer, take the rifle out of its case, and shoot. This infraction had been a simple mistake – I cautioned the guy more strongly about the dangers of having a loaded firearm that everyone would think was unloaded when they got home than about the actual offence. At the end of the day, most of the scouts just shrugged it off – they would arrest someone “because they could”. Authority = Power. One of the greatest ills of Africa today.

One evening we stopped a vehicle with two guys in it. Their rifles were cased and unloaded, but their spotlight was already connected. We gave them a stern warning that the other border was about 50km ahead, and that was where they really wanted to be. Sadly, we had no realtime communication with our South African counterparts unless it had been pre-arranged days earlier, although sometimes we would work with them and the South African Police on the actual border.

On this occasion we didn’t move the roadblock, and most of the rest of the evening passed uneventfully. Until about 01.30 when a pair of headlights approached us from the bush to the east. The car rejoined the main road about 200 metres north of our location, and we hit the blue lights and headlights. The pickup swung around and took off back down the dirt track, but we quickly caught up to them in a pursuit vehicle. Same guys. Hard to imagine. They were out poaching, they had known where we would be, and went out in the bush and got lost. The Klipdrift brandy bottle was empty by now, which may have had something to do with it. There were two boxes of ammo in the front of their car, one of .303 and one of .270. There was not a round to be found, which indicated that they’d ditched those into the bush as they tried to run. Both rifles were hastily cased, with the cases still unzipped. But, technically, cased they were. The spotlight was still connected – they had, of course only been looking for water for a leaking radiator – but they hadn’t managed to shoot anything.

It being a quiet night, we broke the roadblock, took them to the nearest cop shop and detained them. Those were the days of Apartheid in South Africa. There was no Apartheid in any of the homelands. The whites’ holding cell? No, no, you go in that cell there along with everyone else. Basically we had arrested them for stupidity, which probably wasn’t in the statutes. But we knew what they’d been up to and we also knew that once they hit the road the next morning for the safety and sanity of South Africa they would never, ever, be back to shout the odds.

One evening, on a different road, we stopped a pickup truck with four guys in it. Beneath a couple of tarps in the back were a kudu, an impala, and a reedbuck. South Africa was a long way away up the road they’d been travelling, and we were pretty certain where their haul had come from. Behind their seat we found a custom Remington 700BDL .270 with a left-hand bolt – a very expensive piece of kit. The reedbuck was a specially-protected species.

Their story was that they had shot the animals in South Africa on a friend’s farm, but they were in for the whole nine yards – loss of the guns, the vehicle, and for the reedbuck maybe even a spell as a guest of the state if the case went against them. Relatives came and posted bail, and when they returned it was with lawyers. The case went to trial, but we couldn’t prove that the animals had been shot on our turf. Their farmer friend disavowed all knowledge, though, and when it became apparent that we weren’t going to win this one we put a call through to our South African counterpart. We had the sworn statements of all four that they had hunted on a particular farm in South Africa. The farmer denied having given permission, so their defence was effectively that they had poached the animals but not on our side of the border.

The Transvaal nature conservation officer took a sworn statement from the farmer, and we provided copies of all our documentation to him. We had already cost them a small fortune in legal fees, which was some comfort, but I’ll always remember the afternoon when the magistrate dismissed the case and ordered their property returned. As they left the courtroom, there was our opposite number from South Africa holding the rifle and car keys. Across the border, they were convicted on their own defence from our side. The reedbuck was specially protected there as well, and they paid heavily.

One thing about southern Africa’s homelands was that they attracted a lot of interesting characters. The American patents and trademarks clerk looking for expat work with the government who happened to be just a little too good with that Browning 9mm on the range to fit the mould of a boring civil servant. The British newspaper reporter whom no one in British newspaper circles had ever heard of who was also looking for a job, though he appeared he would be more at home on a triathlon course than in some cubicle. Former Rhodesian chopper pilots. Israeli businessmen. I have met a lot of these throughout Africa, and nary a one who wasn’t a spook – although a fellow named Uri I got to know in the Central African Republic some years later and who owned a large diamond mine admitted that spying was only a hobby with him.

We became acquainted with one such visitor who sent us, by way of supporting our cause, a curious little Israeli .22 semi-automatic carbine. It was made to look like a bullpup M16, including a full-sized illusory magazine well that concealed the tiny .22 mag. Having by now put together a reasonably formidable armoury of FN-FALs, South African R1s, and a Ruger Mini-14, we dubbed the little .22 “The Ratkiller” and consigned it – sans ammunition – to one of our more dubious-looking field assistants. The desired effect was achieved – especially in the dead of night on a lonely stretch of road – when this seeming Idi Amin wannabe would emerge ominously from the gloom with what looked like a state-of-the-art weapon system.

Hans’s father Alex came out from the ‘States and worked with us for awhile. A retired US Marshal, he had also served in the Rhodesian Air Force Special Investigations Branch

Unquestionably roadblocks were more efficient than patrols, but we probably still lost more than we caught.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!