Speaking on the range in respect of Practical Pistol shooting with other competitors back in the 1990s when we were on the local competition circuit, we said that the discipline might not really be all that practical in a real world sense in terms of training scenarios, but that it was the best we had. In the context of the times – and many of us had cause to carry firearms in connection with official duties in those days – this was correct. If nothing else, the amount of range time we put in meant that we were infinitely familiar with the vagaries of our firearms, what could go wrong, and the muscle memory required to rectify the problems.

I have done a lot of firearms training for government departments and security companies, and I have always fallen back on coaching the basic fundamentals with Virginia Count standard exercises. The truth is, no departments or companies that I’ve worked with have ever been in a position to offer the degree of comprehensive training that I would have liked to see. And at the end of the day, I have had to ask myself just what I was producing. It wouldn’t be match winners or national team members because you can’t do that on a weekday afternoon with a borrowed gun or a rusty issue Tokarev – that you’ve just had to remove a magazine of 9mm parabellum ammo from because “that was what they had a lot of”. What I want is a basic level of competency. One which can be reinforced by sufficient range time, or built upon by someone wanting to take it to the next level.

So, I believe that a good, old-fashioned standard exercises-style format is ideal for basic firearms training, and later, testing and evaluation. And perhaps few applications for this type of training can be as potentially important as for a professional hunter, whose skill may not only be called upon to save his own life, but the lives of his client(s) and trackers.

Zimbabwe boasts the most comprehensive training regimen for its licensed professional hunters and guides in Africa. Administered through the Zimbabwe Professional Hunters’ and Guides’ Association and National Parks, training for a full license involves a number of written and practical examinations and a couple of years’ apprenticeship served under a fully licensed PH or Guide. Candidates register to sit for one of two National Parks learner licence examinations held each year. Upon successful completion of these exams the aspirant PH undertakes his apprenticeship, during the course of which at least four dangerous game species must be shot. When the candidate has obtained an advanced first aid qualification and passed a shooting proficiency examination and a National Parks oral interview he undertakes the week-long bush proficiency test and if successful will be issued with a full licence – which is renewable annually – by National Parks.

Back in the day, a fairly informal shooting test was incorporated into the proficiency exam – with the caveat that a fail in that component would mean a fail overall. Bush proficiency is a rigorous and expensive undertaking, and it was through the efforts of Dr Don Heath, then an ecologist with National Parks, and police CID superintendent Charlie Haley, that the shooting examination was separated and held as a stand-alone exercise before the proficiency exam. Though you still had to pass the shooting phase before attempting proficiency. Don, at the time being an active IPSC competitor, saw the obvious advantages of using a score-divided-by-time format – in this case Virginia Count – and “major” and “minor” calibre gradings in the training of competent PHs and Guides.

Initially comprising four separate stages which would retain the same format from year to year and test different aspects of firearms skill such as accuracy, fire and movement, and the ability to perform functions like reloading under pressure, the shooting competency tests started off basically as mini-IPSC matches where .375 H&H Magnum was “Minor” (in a separate canoe guides’ test with a handgun, the .44 Magnum is the power floor). Zimbabwe law requires a firearm to generate 5.3 kilojoules of energy at the muzzle and be of a caliber not less than 9.3mm in order to hunt heavy, dangerous game. Therefore, as the 9mm parabellum is the minimum caliber allowed for Practical Pistol, so is the .375 H&H Magnum the minimum caliber allowed for the PHs’ test. (Experienced handloaders can get that 5.3kJ of muzzle energy out of a 9.3 x 62 without too much trouble, but the concept of how the energy is achieved is mostly lost on the authorities and so the “default setting” is accepted as the .375 H&H, though it is not law.)

Any calibre that starts with the venerable number 4 is classed as “Major”, and there is no overall pass/fail in the individual stages that is cast in stone. If, on a particular test day the standard of shooting is better, e.g. the scores are higher and the times faster, the overall bar is raised. Not only would the whole procedure be undermined if the test was not rigorous enough, but there would be no impetus to strive and improve. It is a very common thing to see the same candidates back year after year and the dedicated ones do eventually pass. Many would benefit from a lot more range time and practice and the safari operators they work for could often do much more to help them.

As in an IPSC match, electronic timers are used, a primary range officer closely monitors the shooter and a secondary RO checks for procedural errors. Infractions like unsafe firearm handling or negligent discharges result is a test disqualification. Critical in this sort of scenario – equipment failures are the shooter’s problem as the RO watches benignly as the clock ticks away.

I have been an examiner in these tests for more than a decade, and in that time I have seen a growing number of operators making an effort to see that their apprentices have the time and the resources for practice and improvement and a much larger number of candidates coming onto the range in the days before the exam to iron out any basic technique shortcomings or potential rifle malfunctions. Also, a number of training “boot camps” are now on offer, sanctioned by the ZPHGA.

For a learner PH or Guide, cash is always tight, and many use firearms belonging to whoever they are apprenticed to – which are often in varying states of disrepair – and often ammunition which is completely unserviceable. When I first became involved, by far the biggest problem for the candidates was not their ability to shoot but their often-atrocious equipment that let them down. Ammunition for heavy rifles also does not come cheap, but practice is necessary. Facing a buffalo with your client’s poorly-placed .458 round in its backside is not the time to discover that your rifle’s extractor doesn’t extract or the ejector doesn’t eject. And, if you’re getting your range time in on an airstrip in the Zambezi Valley on your own, you may be practising and cementing bad habits – it’s always good to shoot under the watchful eye of a trained coach or instructor.

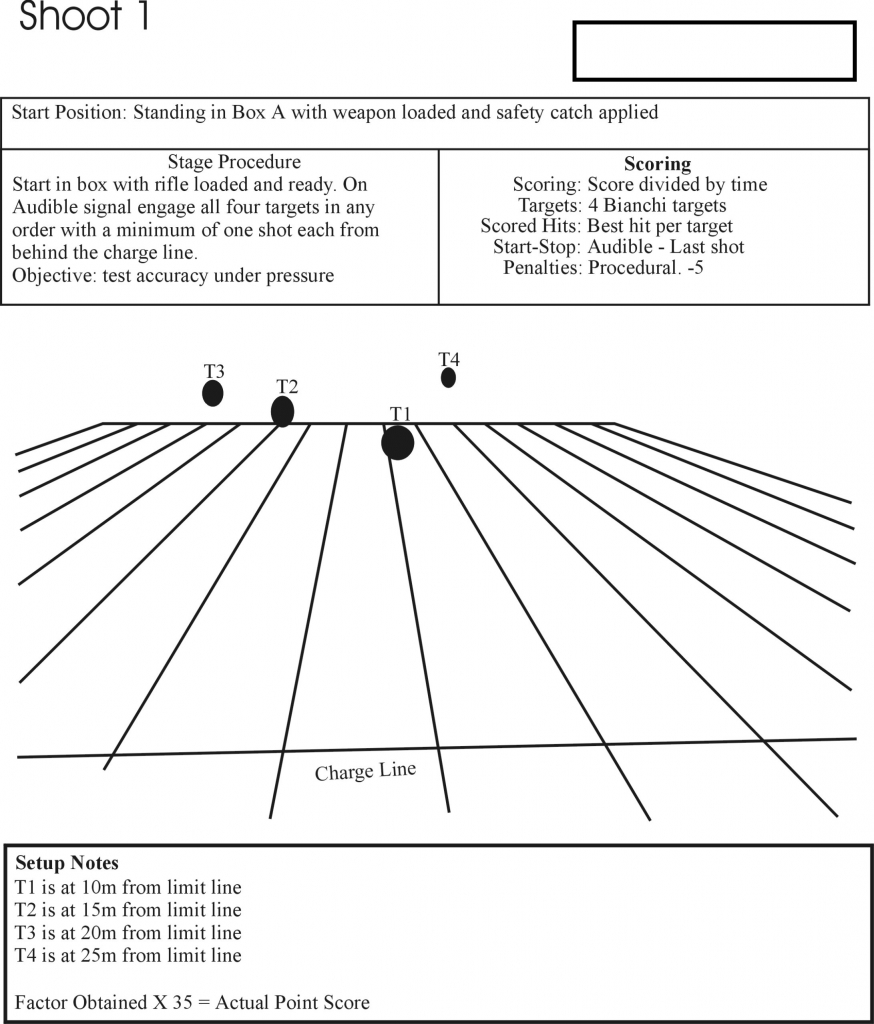

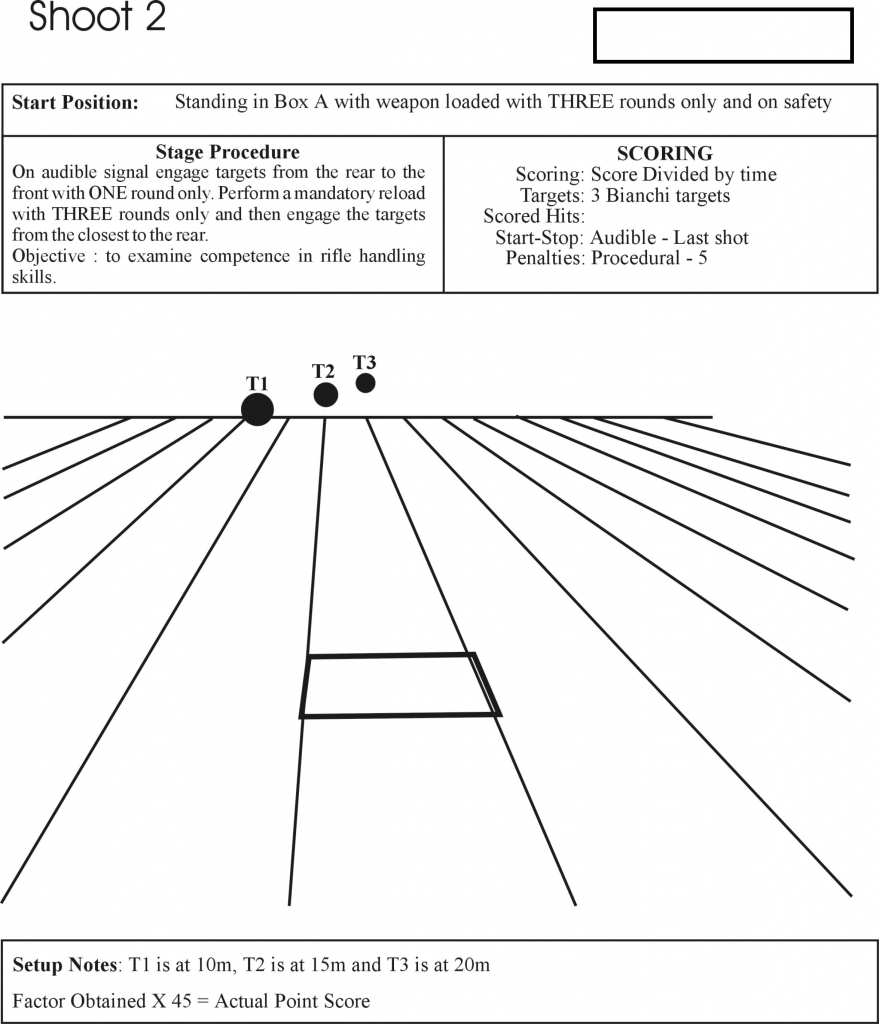

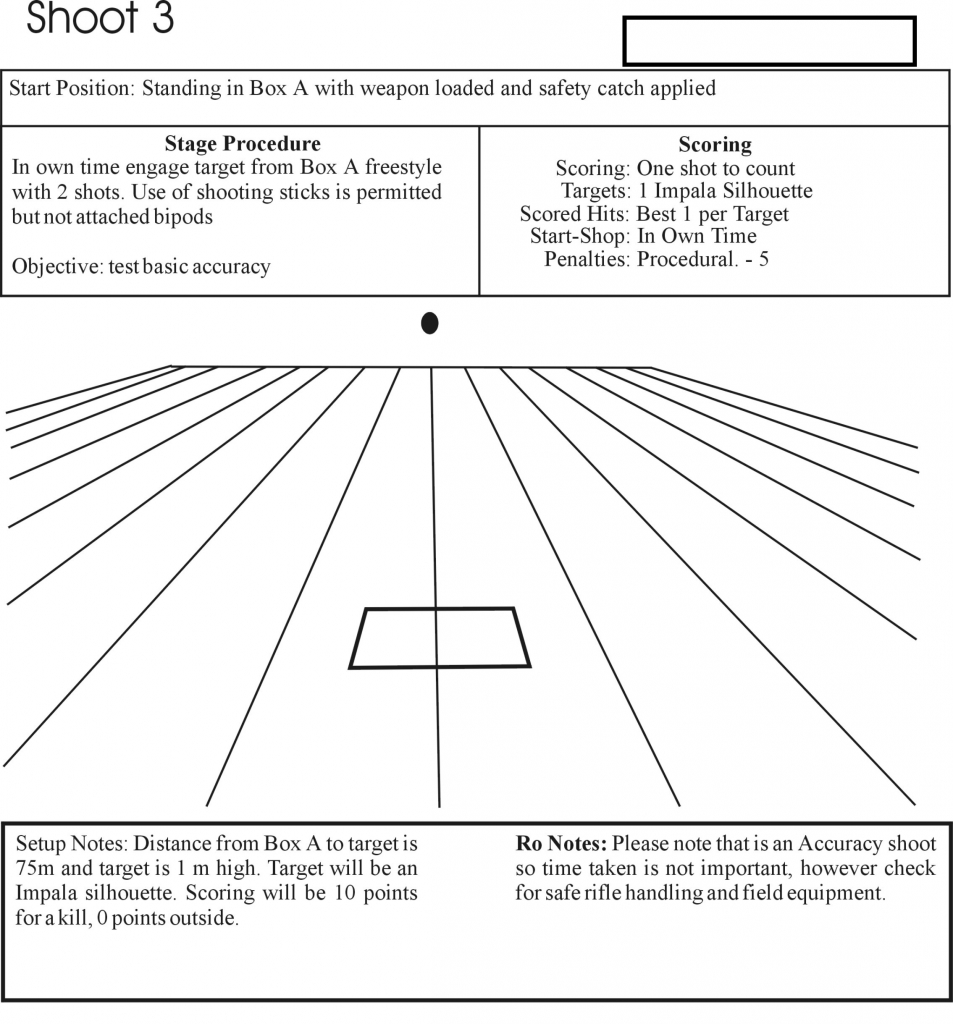

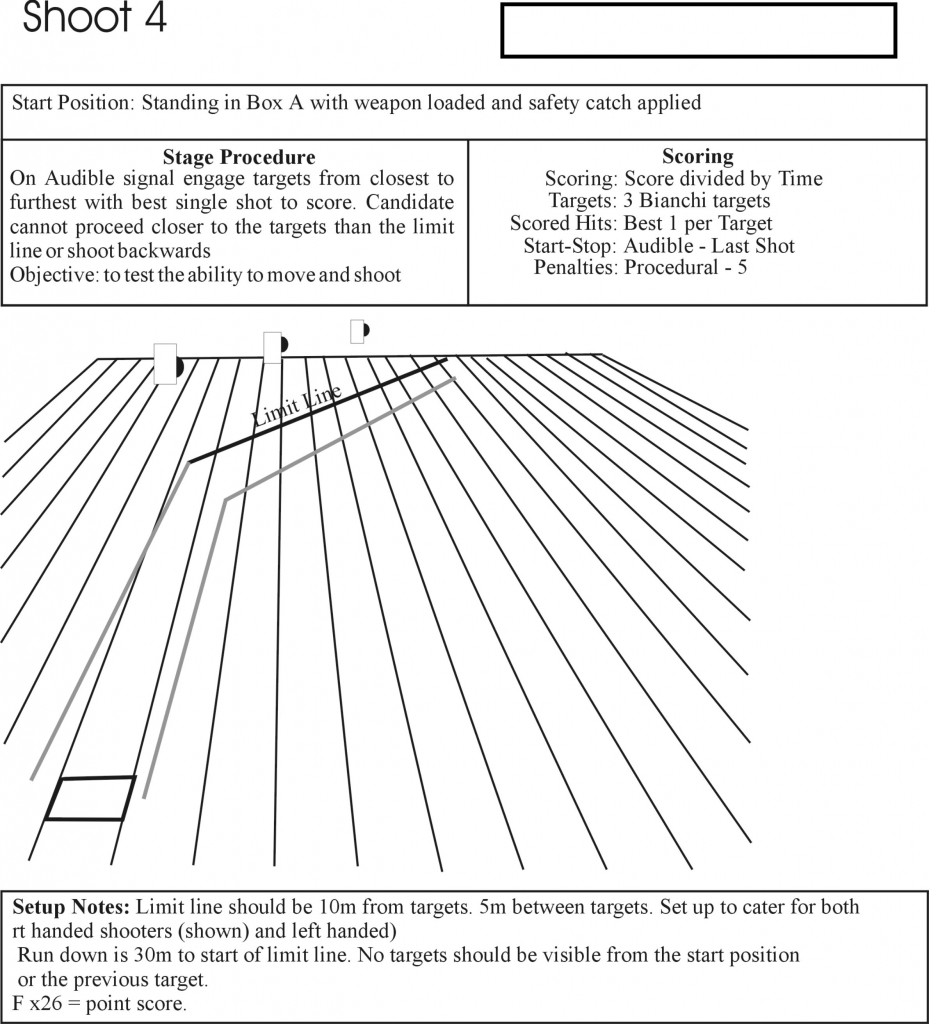

In Stage 1, the run-down, candidates are expected to run to a charge line downrange and then engage four targets at varying ranges with one shot each. This tests the shooter’s ability to compose accurate shots following physical exertion. Stage 2, in contrast, doesn’t require movement by the shooter but it does require two accurate shots to be placed on each of three targets with the pressure of a mandatory reload thrown in halfway – you see a lot of equipment failure on this stage. One would think that Stage 3, the accuracy test, would be points for free. Candidates are required to put two shots on a target at 75m in their own time, using any shooting aids or positions. Surprisingly, it has the highest fail rate. And lastly, in Stage 4 the shooter has to run downrange again, but this time once he is at the charge line he has to stop and start again to engage each of three targets separated by vision barriers.

Good shooting is a result of sound technique and lots of practice. These stages can be run at any time as an informal club match. Many members are licensed PHs and Guides, and I have seen days where some of these doyens – and they are well-known names in the industry – have fared very poorly indeed on the scoreboard. But then, how many PHs really shoot as often as they should? Many members who are not in the industry may be citizen hunters, or just want to shoot something new, with a difference.

Two new additions, introduced by the current chief examiner, ex-National Parks warden Chris Pakenham, are a re-vamped canoe guide’s handgun stage and a simulated charging lion. The Canoe Guide stage requires a minimum calibre of .44 Magnum, and requires the candidate to place six accurate shots on three targets at distances of between 2 and 5 metres within a par time of 8 seconds. The Charging Lion is based on the South African Panterror model, and the shooter must fire 2 shots on the rapidly-advancing target.

It’s a fact that incorporating an element of sporting competition into this type of examination both induces a healthy stress level in the candidates and develops the desire to excel – both of which will benefit them in the end.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!