I was sitting in the pub after a day’s shooting at The Harare Gun Club, and a few of us were discussing “the good old days”. Some things from then were better than others, I suppose. Most of us had shot the local Practical Pistol circuit back in the days when holsters were made out of leather and there was only one division. Courses of fire were more, well, practical.

As the Castle lager – an inspiration for profound philosophical thought – flowed, we hatched a plan to put together a mini-match with some of the Golden Oldies – other than ourselves, that is. More for us, truth be told, than the newer members. The three courses of fire that we decided on were El Presidente, the Mozambique Drill, and Cirillo’s Hostage Shoot. But though these matches are still shot regularly on a lot of ranges, it’s surprising how many folks don’t understand their history and why they remain some of the best training drills out there.

I should mention here that having trained armed security guards and government law enforcement details for almost three decades, I am a big fan of the basics: stance, grip, sight picture and trigger control. Repeated ad nauseam until it became second nature. I look askance at the sport shooter-concept of taking people like that and teaching them to kick doors in, run down passages, &c., on the range. Walk, then run. But the drills I am discussing here are really suitable for anyone, pistol or revolver, and by introducing a spirit of competition and making people shoot against a clock for a score you engender camaraderie and interest.

The El Presidente is considered to be the classic training drill by us walking anachronisms. It is an exercise developed by the late Col Jeff Cooper, who was the innovator of all that passes today for “practical” shooting sports, and indeed the lion’s share of the principles of modern handgunning, including holding the firearm with two hands. He was the founder of Gunsite, aka the American Pistol Institute, which was the first modern private firearms training facility in the US, and the best in the world. He was the guiding light of the 1976 Columbia Conference, at which modern IPSC shooting was born, and he was the first President of IPSC. With comments like “The organisers of the competition (an IPSC world championship match held in South Africa in the early ‘80s) have erred insofar as there is any such thing as a competition holster” he gradually grew more and more estranged from the sport shooting disciplines like IPSC, but for the “old guard” he remains, well, Yoda.

While training close protection details for the president of a Latin American country, Cooper created the El Presidente. It was intended to achieve two things: to train shooters in a wide range of basic skills, but, more importantly, to measure their progress over time.

To set up the classic El Presidente, place three targets in a line downrange, three metres apart. The shooter commences the drill standing ten metres uprange, and facing away from the targets, with hands shoulder-high in the position of surrender. On the audible start signal, the shooter turns toward the targets, draws his firearm (from concealment in the original incarnation) and engages each target with two rounds. The shooter then reloads and re-engages each target with two rounds. This is what is today known as a Virginia Count exercise: timed, but with a stipulated number of rounds – the shooter may only fire 12 rounds.

El Presidente is simple to set up, shoot and range, but it brings into play every skill needed for proficient self-defence – the draw, the reload, movement, and engaging multiple targets. Cooper considered par to be a perfect score in ten seconds, but I have seen it done in half that. The perfect score is important. When the shooter sacrifices accuracy to beat the clock, the drill loses much of its relevance. It’s worth mentioning here that the drill may be done either score divided by time, or within a pre-set par time.

The modern El Presidente commonly has the targets one metre apart, concealment is no longer required, and the shooter must change direction for his second string after the reload, but no one will complete the drill creditably unless their gun-handling skills are good. El Presidente also tests your gun and equipment, and when I said earlier it is also a measure of progress, the whole idea is to get that perfect score down in less and less time as you become more proficient from other drills. If you are doing that your skills are improving. If you practice it every weekend until you are like a machine it is more difficult to use it to gauge overall progress.

In order to become a proficient pistolero, you need to put in constant practice. A lot of the basics can be polished with dry fire exercises and then cemented with live fire on the range. El Presidente was the first modern combat training drill, and it is still very relevant.

The Mozambique Drill is another time-honoured classic. The 1976 Practical Pistol world championships in Austria, though held under the banner of the newly-formed International Practical Shooting Confederation, was shot as a “combat” pistol match. In the days before political correctness was inflicted upon us, and targets resembled humanoid silhouettes rather than pizza boxes, and especially in Africa, the mantra “two to the body and one to the head” was oft heard on the range. This has its origins in a defensive course of fire called the “Mozambique Drill”. Sometimes also known as the “Failure Drill”.

During the Mozambican War of Independence, which lasted just under a decade, from 1964 to 1974 between the soon-to-be former colonial power Portugal and the Mozambique Liberation Front, a mercenary named Mike Rousseau was one of the combatants on the Portugese side. Rousseau was engaged in a firefight at the airport in Lourenco Marques, now Maputo, and at one point, Rousseau’s primary weapon was a Browning 9mm handgun. As he came around the corner of a building he found himself facing an insurgent armed with an AK-47. Rousseau brought up his pistol and fired two rounds, centre of mass, into his opponent’s chest. The FRELIMO soldier not only did not go down, but he did not lose his AK, either. Rousseau had lowered his pistol to the ready position but now decided to fire a third shot to the man’s head. In the heat of combat, his third round hit the insurgent in the throat. Nonetheless, it broke the spinal cord and ended the fight.

Shortly thereafter Rousseau made the acquaintance of Col Cooper. When told of the encounter with the insurgent Cooper realised a great embryonic training drill when he saw one. He named it the Mozambique, and by the late 1970s, it was part of the training regimen at Gunsite.

In 1980 two Los Angeles Police SWAT officers enrolled in a week-long pistol course at Gunsite. They liked the Mozambique Drill, and appreciated its superiority as a fight-stopper. With Cooper’s blessing it became incorporated into the LAPD’s curriculum. In the interests of political correctness, it was re-christened the “Failure Drill”. Even simpler than the El Presidente, it originally consisted of firing two shots at the centre of body mass, lowering the pistol to the ready position and assessing the need for the third shot. Soon the return to the ready position was modified to a straight transition from the centre of mass to the head. Why an experienced combatant like Rousseau had not done this is anyone’s guess. Maybe he had.

In today’s world there are lots of reasons why two shots to the centre of mass won’t necessarily neutralise a target: poor choice of calibre or poorly-performing ammunition, body armour, heavy clothing, or a drug-induced high. It doesn’t really matter why in a gunfight, the critical need is to end the encounter.

Rounds fired centre of mass should end an attack by disrupting blood flow to the brain, or damaging the criminal’s spinal cord; damage to the lungs is secondary, but significant nonetheless. But if they don’t, the aggressor still poses a deadly threat. While the intention should not be to kill, but rather to end the threat, a bullet to the head will probably conclude the fight immediately.

Today’s Mozambique/Failure Drill is done by firing two shots to the centre of mass and one to the head as quickly as possible. This is a range exercise, so the clock will be running, and the distance to the target can be anywhere between five and fifteen metres – or even farther, depending on the shooters’ skill levels. Again, it is Virginia Count, so the stated course of fie must be followed and no more than three rounds may be fired. The two rapid shots to the centre of mass present very little challenge to anyone who is proficient with their firearm, but the trick is then to slow down just that little bit to get a precise head shot.

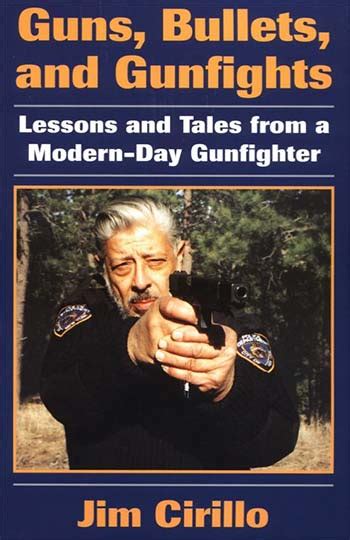

The late Jim Cirillo was a big advocate of as much rangetime as you could possibly put in, and he was also very favourably disposed to the pistol shooting sports. But why his name might be familiar to many shooters is that he was a blooded veteran of the New York Police Department’s famed Stakeout Squad. He was the author of the book Guns, Bullets and Gunfights, and the book Jim Cirillo’s Tales of the Stakeout Squad was the biography written about him by American author Paul Kirchner. Both are available from Paladin Press. Jim Cirillo was never an armchair anything when it came to firearms. In over 250 stakeouts, he was involved in more than 20 gunfights, and killed at least 11 perpetrators. So a drill based on his experiences carries some credibility.

The Cirillo’s Hostage Shoot replicates an encounter Cirillo had with three armed robbers in a supermarket; as they tried to flee, one only exposed his head briefly, and two were obscured by a cashier. Cirillo fired six rounds from his Smith and Wesson M10 .38 Special revolver in what the re-enactment deemed to be about three seconds, taken from Cirillo’s own estimate. All the robbers were hit, and one died at the scene. We’re probably all familiar with the History Channel video clip of Jerry Miculek engaging three targets with a revolver, El Presidente-style without the turn and firing 12 rounds on target in three seconds including the reload, but none of them were shooting back at him. Cirillo commented afterwards about the three seconds, “I’ve spent so much time on the combat range I ought to know!”

To set up Cirillo’s Hostage Shoot, you arrange two targets – the current International Defensive Pistol Association 18” x 30” silhouette target is probably the best for all these drills – at a ground-level position, and superimpose between them a designated no-shoot target to represent a hostage. Place this target array at 7 metres. Then, at 10 metres and 90o to one side (bearing in mind your range’s safety angles) place another target which either has only the head portion exposed or conversely only head shots will be counted. Again it is a Virginia Count exercise, with a time of three seconds for one scoring hit on each target being the goal, or score divided by time.

The above three stages make for a challenging but not overly-complicated mini-match, or personal training drill. The total round count is 18, and by either setting a more generous par time for the Cirillo’s Hostage shoot or just recording the shooter’s time as it is rather than use a par feature on the timer it can be quick and fun for shooters of all skill levels.

And a good starting point from which to gauge future progress.

Originally published in MAN Magnum Magazine, December, 2017

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!